Discover the architectural marvel of the 13th century BCE with the Lions’ Gate in Mycenae, where art meets structural innovation.

The journey of classical tradition, from its origins in ancient Greece during the 5th century BCE to its spread in Rome, the Renaissance, and the modern world, often appears as a straight line. However, its roots are incredibly complex and trace back to a time of turmoil. Following the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization, the Greek region plunged into a period that historians refer to as the “Dark Ages,” a time when monumental architecture and intricate arts seemed to fade away, giving way to simpler and more abstract forms of expression. Yet, through this period of silence, a new, strict, and mathematically organized aesthetic was born, which, although it may initially seem simplistic, laid the groundwork for the entire subsequent evolution of Western art, shaping a world where order and harmony would prevail. This is the story of Geometric art. But how did this art, with its strict lines and repetitive patterns, become the precursor to classical perfection? The answer lies in the fragments of pottery and the few architectural remnants that survived. The very familiarity of Greek art may lead us to take the beginning of narrative art for granted (Carter).

The Emergence of a New Aesthetic: From Proto-Geometric to Mature Geometric Period

The dawn of the Iron Age in Greece, around the 10th century BCE, marks a pivotal moment. It is not merely a technological transition. It represents a cultural renaissance primarily expressed in clay. In Athens, which early on emerged as a pioneering artistic center, artisans began to experiment with new forms and decorative principles, consciously moving away from any surviving Mycenaean heritage. The pottery found in graves from this period, known as Proto-Geometric, reveals a remarkable transformation. The simpler, curvilinear Mycenaean patterns disappear. In their place emerges a strict, almost puritanical geometry. Artisans, using multiple comb-like brushes, render old designs with unprecedented precision, creating concentric circles, semicircles, and parallel lines that embrace the surface of the vessel with rhythm and order.

The technique improves dramatically. Potters, perfecting the ceramic wheel, create shapes that are sturdier, more harmonious, and efficient in use, while decoration is no longer a random element but is fully integrated and highlights the structure of each vessel, emphasizing the neck, belly, or handles. Simultaneously, painters develop the technique of shiny black paint, which, when fired at high temperatures, acquires a glossy, metallic appearance, gradually covering larger surfaces and creating a striking contrast with the light-colored clay. This period, despite its simplicity, is revolutionary. It establishes the rules of a new language, where logic and order prevail over emotion, a language that will be enriched and dramatically evolve in the coming centuries. The history of Greek art is filled with such moments of rupture and reconfiguration (Stansbury-O’Donnell).

As time flows and we move into the 9th century BCE, decoration becomes more elaborate and complex. Artists, having fully mastered the basic geometric shapes, begin to introduce new themes, tentatively at first, bolder later. Stylized birds and, primarily, horses appear in the bands of the vessels. Why the horse? Perhaps because it represented wealth, speed, and the aristocratic class of warriors that dominated this society. However, these forms are not naturalistic. They are entirely integrated into the geometric logic, composed of triangles, lines, and curves, as if they too were merely another decorative motif, an exercise in abstraction. And then, the human form appears. Initially as a silhouette, with a triangular torso, round head, and linear limbs, a figure that resembles more a symbol than a depiction.

The climax comes in the 8th century BCE, during the Mature Geometric period. Decoration becomes ambitious, almost frenzied. On certain monumental vessels, such as the enormous amphorae and kraters that served as markers in graves at Dipylon in Athens, geometric patterns—meanders, zigzags, diamonds—cover the entire surface in multiple, dense bands, creating a sense of “horror vacui,” the fear of emptiness. Not a single inch remains uncovered. Within this dense web, however, human figures take center stage and for the first time are organized into narrative scenes. We see the intention, the funeral procession where the deceased lies on a funeral bed surrounded by mourners tearing their hair in grief. We see chariot races in honor of the dead. We see battles, with warriors holding double-bellied shields clashing in a battlefield defined by the very geometric order. These scenes, although abstract and schematic, are the first great narrative compositions of ancient Greek art, the distant ancestors of the metopes of the Parthenon. The relationship between nature, art, and geometry in Greece has since become a lasting field of research and admiration (Papathanassiou). Accepted and conventional views of Greek art are often merely academic survivals from a distant past (Ivins Jr).

Beyond Pottery: Architecture and Metalwork in the Dark Ages

Although geometric pottery dominates our perception of the period, artistic creation was not limited to clay. Architecture, though on a smaller scale compared to Mycenaean palaces, presents exceptional interest, with Euboea offering a unique window into this era. In the settlement of Lefkandi, archaeological excavations uncovered an imposing building, dating around 1000 BCE. It was a massive, apsidal structure, nearly 50 meters long, built of mud bricks, wood, and stone foundations. Its significance, however, lies not only in its size, unprecedented for the time, but also in its use. In the center of the building, two rich graves were found: that of a warrior man, whose ashes were kept in a bronze amphora from Cyprus, and that of a woman adorned with gold jewelry. This finding suggests that the building was not a simple residence. It was likely a hero shrine, a place of worship dedicated to a local leader after his death, or perhaps the very palace that was transformed into a funerary monument.

The grave goods, objects from the East and Egypt, reveal that, despite the insularity of the Dark Ages, Euboea, due to its strategic position in the Aegean, maintained trade and cultural contacts. The building at Lefkandi, although unique, connects Mycenaean heritage with new architectural trends, foreshadowing the apsidal layout that we will later encounter in early temples. Meanwhile, metalwork flourishes. Small bronze figurines of horses and humans, with the same strict geometric logic seen in the pottery, serve as valuable offerings in sanctuaries like Olympia. The bronze work of the Geometric period and its relationship with later art reveal a gradual escape from strict conventions (Casson). It is striking how little we know about the art of the period beyond pottery, as large figurines, primarily made on the potter’s wheel, have been found in various Greek locations of the late Bronze Age, and this may be a field where future discoveries will surprise us, as noted in a related study (Robertson). This period, long considered stagnant, ultimately proves to be a time of ferment and fundamental changes, where Geometric Greece laid the foundations for the great Orientalizing movement that would follow (Coldstream).

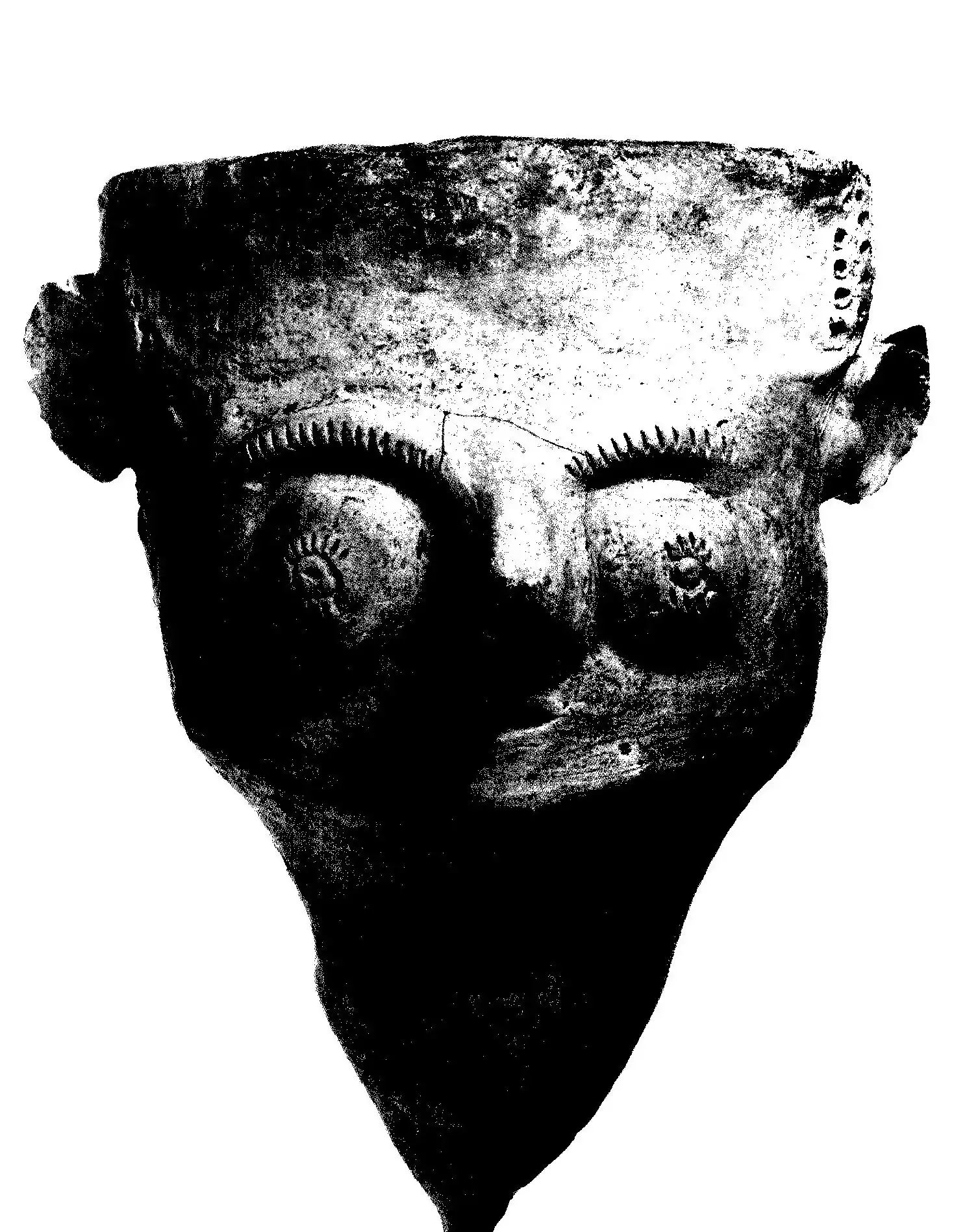

Janiform clay head from Crete, 10th/9th century BCE, featuring a male and a possible female face, used as a cult idol or offering vessel.

Society, Symbols, and Narrative: Decoding the World of Geometric Art

Art never emerges in a vacuum. It is a reflection of the society that creates it, a code that captures its values, fears, and aspirations. Therefore, to truly understand the strict, almost cerebral aesthetic of the Geometric period, we must look beyond the meanders and spirals and ask: who were the people who commissioned and created these works, and what were they trying to convey? The answer lies in the very function of the most emblematic creations of the time, the colossal vessels of Dipylon. These masterpieces were not merely decorative objects. They were markers. Monumental grave markers, placed over the tombs of the Athenian aristocracy, an elite that, after centuries of turmoil, was beginning to reorganize and establish its dominance within the nascent city-state. They were statements of power.

In this context, the intricate narrative scenes that adorn them acquire a deeper meaning. The scene of the intention (the display of the deceased) is not just a record of mourning but a public display of the wealth and social status of the family, which could afford the resources for such an elaborate funeral ceremony and, above all, for such a monument. Each figure, from the deceased lying majestically on the funeral bed to the crowd of mourners surrounding him with their hands on their heads in a gesture of standardized grief, contributes to the glory of the house. Even more, the scenes of chariot races and battles that often occupy the lower zones serve as a visual eulogy, extolling the virtues of the deceased as a warrior and leader, linking him to the heroic ideal celebrated in the Homeric epics, which at that very time were beginning to crystallize in written form. Art and poetry walked hand in hand. The effort to understand the rich cultural matrix within which Greek art developed is fundamental (Stansbury-O’Donnell).

The human form itself becomes the bearer of this narrative. Yes, it is schematic. The torso is an inverted triangle, the head a circle with a dot for an eye in strict profile, the legs and arms are simple lines, swollen at the calves and thighs to indicate volume. There is no attempt at realism or individualization. All forms look alike, distinguished only by subtle elements indicating gender or role. However, through this absolute abstraction, geometric artists achieved something revolutionary: they created a clear and readable visual code capable of conveying complex narratives. The absence of realism is not a weakness. It is a conscious choice that emphasizes the action and structure of the scene, rather than the individual characteristics. The beginning of narrative art in Greece was based on these very isolated silhouettes and processions that resembled matches (Carter).

As the 8th century progresses, narratives become bolder, and scholars debate whether some of them depict specific myths. Is the figure holding two warriors joined at the waist a reference to the mythical twin Moliones? Is the scene of a shipwreck, where a man clings to the overturned hull of a ship, an early depiction of Odysseus? The answers are uncertain. However, the mere existence of the question proves that artists were beginning to explore the boundaries of their art, transitioning from the general depiction of aristocratic life to the specific illustration of mythology, a transition that would define Greek art for the coming centuries. The deep connection between art and geometry forged then became the foundation upon which the entire classical edifice was built (Ivins Jr). This obsession with order, rhythm, and mathematical precision would soon explode into something entirely new.

By the end of the 8th century BCE, a new wind begins to blow in the Aegean. The gradual exit from the Dark Ages, the establishment of colonies in the West, and the increasing trade contacts with the cultures of the Near East—Phoenicians, Assyrians, Egyptians—bring with them not only new products but also new ideas, new technologies, and, above all, a new, exotic iconographic vocabulary. The strict, introspective, and rational world of Geometric art begins to receive influences. The change is sweeping and marks the transition to the Orientalizing period. The rigid geometric lines begin to bend, becoming curves. On the surfaces of vessels, alongside traditional meanders, fantastic creatures from the East invade: sphinxes, griffins, sirens, and imposing lions. The fear of emptiness recedes, compositions become more sparse, and forms gain more space to breathe and move. Geometric Greece, after two centuries of artistic introspection, opened its windows wide to the world (Coldstream). The human figure itself transforms. The technique of black silhouette remains, but now artists begin to use incision to render details such as muscles, hair, and folds of clothing. Bodies become more fleshy, more organic, heralding the monumental plasticity of the Archaic period. The Geometric period, therefore, was not the end of a world but the necessary, long, and arduous preparation for the birth of a new one. It was the school of order and narrative. It was the foundation.

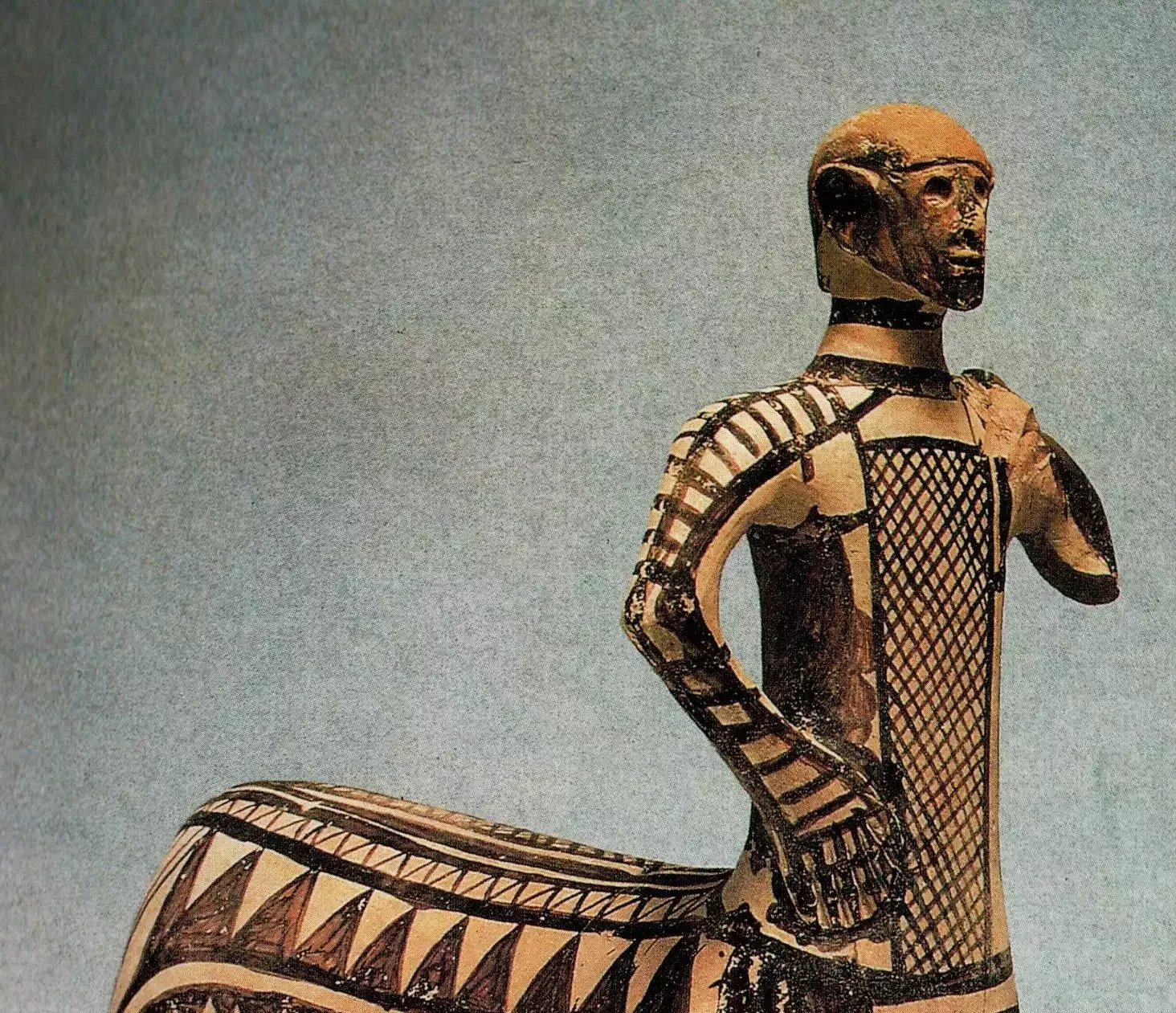

Ancient clay centaur from Lefkandi, around 900 BCE, showcasing early and eastern influences, promoting the art of centaurs in ancient Greece.

Bibliography

Carter, J., ‘The beginning of narrative art in the Greek Geometric period’, Annual of the British School at Athens, (1972).

Casson, S., ‘Bronze Work of the Geometric Period and its Relation to Later Art’, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, (1922).

Coldstream, J.N., Geometric Greece: 900–700 BC, (2004).

Ivins Jr, W.M., Art & geometry: a study in space intuitions, (1946).

Papathanassiou, M.K., ‘Nature, Art, and Geometry in Greece’, Tome 1: Manuscripts.› Codices‹, Texts…, (2025).

Robertson, M., A Shorter History of Greek Art, (1981).

Stansbury-O’Donnell, M.D., A history of Greek Art, (2015).