Ivory figurine representing a female form, serving as a decorative mirror handle, found in a tomb in Athens, dating back to the 8th century BC.

The history of copper in ancient Greece (Treister) is one of the most crucial factors in shaping Greek culture from the Mycenaean period (1600-1100 BC) to the Classical era (5th-4th century BC). This metal acted as a catalyst for cultural changes. The copper trade routes (Maddin, Muhly) established communication networks that transcended the geographical boundaries of Greece, while the metallurgy of copper and bronze (Papadimitriou) laid the foundation for the development of specialized technical communities that significantly influenced Greek artistic production.

The Geopolitical Aspect of Copper Art

The Greek peninsula, with its limited copper resources, was compelled early on to develop complex trade networks. This necessity transformed into an opportunity for cultural enrichment, as Greek traders traveling to Syria, Cyprus, and Asia Minor for copper procurement returned not only with the precious metal but also with new techniques, aesthetic concepts, and symbolic systems that were organically integrated into Greek tradition. The ancient Greek trade networks (Kron) created an early form of globalization that connected the Mediterranean with the Near East. The strategic importance of these trade relations is evident from the fact that metals in the ancient world (Finley) were subject to strict state control, particularly regarding copper, which was essential for producing weapons and tools.

This phenomenon had direct implications for social stratification. Access to copper determined the hierarchy of power, as those who controlled the sources and processing techniques held a military advantage. Therefore, copperworkers were not merely craftsmen but crucial social agents, and their workshops served as centers of both economic and cultural activity.

The Symbolic Role of Copper in Religious Practices

Beyond its practical utility, copper acquired profound religious and symbolic significance in the ancient Greek world. The bronze cauldrons dedicated to the sanctuaries, particularly in Olympia and Delphi, were not just offerings but carriers of multi-layered messages. The Cycladic metallurgy and the early Bronze Age (Renfrew) reveal that by the 3rd millennium BC, specialized workshops were already producing ritual objects with specific symbolic functions. The metal, shiny and durable, was associated with the concept of eternity and divine presence, which is why most sacred objects were made of copper or its alloys.

The theological dimension of copper in ancient Greek thought is closely linked to the perception of the metal as a means of transformation and purification. In mythological tradition, Hephaestus, the god of metallurgy, is not merely the protector of copperworkers but a symbolic representative of the creative force that transforms raw material into cultural products.

The Encounter with Eastern Ivory

The relationship between copper and other luxurious materials, such as ivory, reveals the complex nature of cultural exchanges in the ancient world. The early Greek and Oriental ivories (Barnett) of the 8th and 7th centuries BC were combined with bronze elements to create complex artistic works that reflected the international nature of the elites of that time. Ivory, primarily imported from Syria, complemented copper, creating polychromatic and multi-material compositions that expressed the aesthetic quest for harmony through contrast.

The use of ivory in ancient Greek sculpture (Nováková) tradition reveals the deep understanding of the physical properties of materials by ancient Greek artisans and their creative utilization to achieve specific artistic goals.

Island Metallurgy and Technological Innovation

Particular mention should be made of the copper metallurgy in Thassos (Nerantzis, Bassiakos, Papadopoulos), which during the Early Bronze Age (3rd millennium BC) developed techniques that would influence the entire northeastern Mediterranean. Archaeological findings reveal that Thassian metallurgists did not limit themselves to simple copper processing but experimented with arsenic and tin alloys, paving the way for the development of bronze technology.

This innovative aspect of Greek metallurgy reflects the broader mindset of ancient Greek culture towards technology and art. The Greeks did not confine themselves to passive assimilation of foreign techniques but transformed them into springboards for further innovations.

Artistic Expression and Aesthetic Philosophy of Copper

The second dimension of the relationship between ancient Greece and copper concerns its transformation from a simple functional material into a medium of artistic expression. This metamorphosis was not merely technical but philosophical, reflecting the Greek perception of the relationship between matter and spirit, practicality and beauty.

From Tool to Work of Art

The evolution of copper art from the creation of simple tools and weapons to the production of sculptures, statues, and decorative objects captures the gradual spiritual maturation of Greek culture. The bronze vessels of the 7th century BC, with their intricate geometric patterns and Oriental influences, were no longer merely utilitarian objects but carriers of aesthetic and symbolic messages appealing to both the senses and the intellect.

The transmission of color from metals and ivory to ceramics (Vickers) reveals another significant factor: the influence of luxurious materials on the development of new aesthetic standards that permeated various artistic mediums. Thus, the aesthetics of copper were not confined to metallic objects but extended to other arts, creating a unified artistic code that characterized Greek production.

This process of aesthetic transmission reflects the deep Greek belief that beauty is not merely an external characteristic but an internal principle that can be expressed through different materials and techniques while maintaining its unity.

Theoretical Approach to Copper Art

The significance of copper in ancient Greek culture extends beyond its practical applications to encompass theoretical thought about art and technology. Ancient Greek philosophers, from the Pre-Socratics to Aristotle, recognized metallurgy as a field where nature and metaphysics, matter and form, potential and actuality intersect. The process of casting, where metal transforms from solid to liquid and then returns to a solid state acquiring a new form, was used as a model for understanding natural processes and human creativity.

Thus, copper in ancient Greece transcended the boundaries of a mere material to become a symbol of human capacity to transform nature and create new realities through the synthesis of technical skill and spiritual insight—a philosophy that would remain pivotal for the development of Western aesthetic thought.

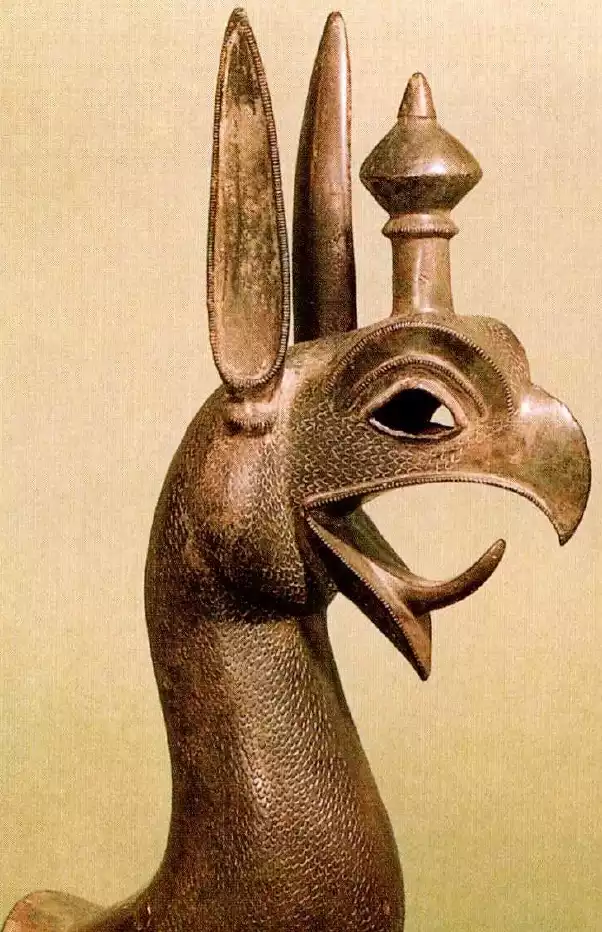

Bronze griffin heads hung from the rim of large cauldrons in an Eastern style, dedicated to Greek sanctuaries. They are Greek cast imitations of Syrian hammered prototypes from the 7th century BC. Found at the archaeological site of Olympia.

The Timeless Legacy and Spiritual Heritage of Copper

From Antiquity to Modern Consciousness: A Cultural Continuity

The deeper significance of copper in ancient Greek culture transcends the temporal boundaries of antiquity, constituting a timeless cultural phenomenon that continues to shape modern understanding of the relationship between technology, art, and spirituality. It is not merely a historical past but a living heritage that contains profound lessons about the nature of human creativity. The study of ancient Greek commercial activity (Kron) in a comparative perspective reveals that the principles governing the Greek approach to metallurgy—the synthesis of practical application with aesthetic pursuit, openness to foreign influences while maintaining cultural identity, and viewing technology as a means of spiritual expression—remain relevant today, offering an alternative model to the contemporary technological orientation that tends to separate technique from spiritual dimension.

This timelessness is particularly evident in the way modern archaeological research approaches bronze findings, not merely as technical objects but as multi-dimensional texts that reveal the deeper structures of ancient Greek worldview and its relationship with the material world, nature, the divine, and social organization—a interpretative approach that highlights the importance of cultural framing in understanding historical phenomena.

The Theological Dimension and the Sacralization of Matter

Of particular importance is the theological dimension attributed to copper and metallurgy in ancient Greek thought, reflecting a much deeper philosophical stance regarding the nature of matter and human creative activity. The connection of Hephaestus with metallurgy is not merely a mythological personification but a theological framework that recognizes technical activity as a participant in divine creative energy. This perception transcends the Western distinction between sacred and profane, considering human technique as a continuous and integral part of cosmic order.

The sacralization of copper in ancient Greek sanctuaries, through the dedication of bronze objects to the gods, also reveals a profound understanding of the material dimension of religious experience that opposes abstract and immaterial approaches to the divine. For the ancient Greeks, the divine was not merely a spiritual reality but a force manifested through physical matter and human technique, and copper, with its special relationship to light and durability over time, served as a privileged medium for this theophany. This theological approach, recognizing the spiritual dimension of material reality, offers significant lessons today for addressing the ecological crisis and developing a more holistic relationship with the natural world.

Cultural Synthesis and the Global Dimension of Hellenism

The analysis of the relationship between ancient Greece and copper highlights one of the most significant characteristics of Greek culture: the ability to synthesize and transform foreign influences into organic elements of its own identity. Research on ancient Greek and Oriental ivory works (Barnett) shows that cultural exchanges were not limited to passive assimilation but constituted a creative process that produced new artistic forms and aesthetic categories. This phenomenon reveals a deeper philosophical attitude towards cultural otherness characterized by openness, trust in its own creative dynamics, and the ability to engage in dialogue.

Copper acted as a catalyst for this cultural synthesis. Trade journeys for its procurement created communication networks that transcended national and cultural boundaries, while the technical workshops processing it became spaces for meeting and exchanging expertise among different cultural traditions. Thus, Greek copper art was not merely Greek but a result of multicultural collaboration that nonetheless retained the Greek spiritual imprint.

Ancient pendant jewelry in the shape of a crescent from Minoan Knossos shows human and bird forms. The eyes of the decorative representation contained amber paste. Dated to 800 BC.

The Timeless Message: Towards a Holistic Understanding of Technology

The legacy of copper in ancient Greece offers modern times an alternative model of thought regarding the relationship between technology, culture, and spirituality that opposes the prevailing trend of technological determinism and the disconnection of technique from broader human values. For the ancient Greeks, metallurgy was not merely a technical activity but a spiritual endeavor encompassing philosophical, theological, and artistic dimensions, while also serving as a means of social cohesion and intercultural communication.

This holistic approach to technology, which integrates it into the entirety of human experience rather than isolating it as an autonomous domain, can provide significant lessons for addressing contemporary challenges. The relationship of the ancient Greeks with copper demonstrates that technological development is possible without sacrificing human values at the altar of efficiency but rather enhancing and enriching them. In an era where artificial intelligence and new technologies raise profound questions about the future of human creativity, the ancient Greek experience with copper shows that true technological progress does not consist of replacing humans with machines but in the creative synthesis of human wisdom and technical skill.

Ultimately, copper in ancient Greece represents much more than a mere material or technological achievement: it symbolizes an entire cultural philosophy that recognizes the interdependence of all dimensions of human existence and seeks their harmonious synthesis. This legacy, preserved in the bronze artworks that have reached us, continues to inspire and guide those seeking a more human and spiritually enriched way of life in the modern world.

Bibliography

Barnett, R.D. (1948). ‘Early Greek and Oriental Ivories’, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 68, pp. 1-25.

Finley, M.I. (1970). ‘Metals in the ancient world’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 118(5164), pp. 597-612.

Kron, G. (2016). ‘Classical Greek trade in comparative perspective’, in Harris, E.M. et al. (eds.) The Ancient Greek Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 356-380.

Maddin, R. and Muhly, J.D. (1974). ‘Some notes on the copper trade in the ancient Mid-East’, JOM, 26(4), pp. 17-23.

Nerantzis, N., Bassiakos, Y. and Papadopoulos, S. (2016). ‘Copper metallurgy of the Early Bronze Age in Thassos, north Aegean’, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 7, pp. 335-348.

Nováková, L. (2023). ‘Making Gods in Ancient Greece: Rituals and Cult Images Development Through Tracing Ivory Use in Statuary Tradition’, in Contact, Circulation, Exchange: Proceedings of the Conference. Prague: Charles University Press, pp. 115-132.

Papadimitriou, G. (1991). ‘Copper and bronze metallurgy in ancient Greece’, Archaeometry, 33(2), pp. 181-198.

Renfrew, C. (1967). ‘Cycladic metallurgy and the Aegean early Bronze Age’, American Journal of Archaeology, 71(1), pp. 1-20.

Treister, M.Y. (2018). The role of metals in ancient Greek history. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vickers, M. (1995). ‘Surface colour transfer from metal, ivory and stone to ceramic and glass’, MRS Online Proceedings Library, 352, pp. 189-194.