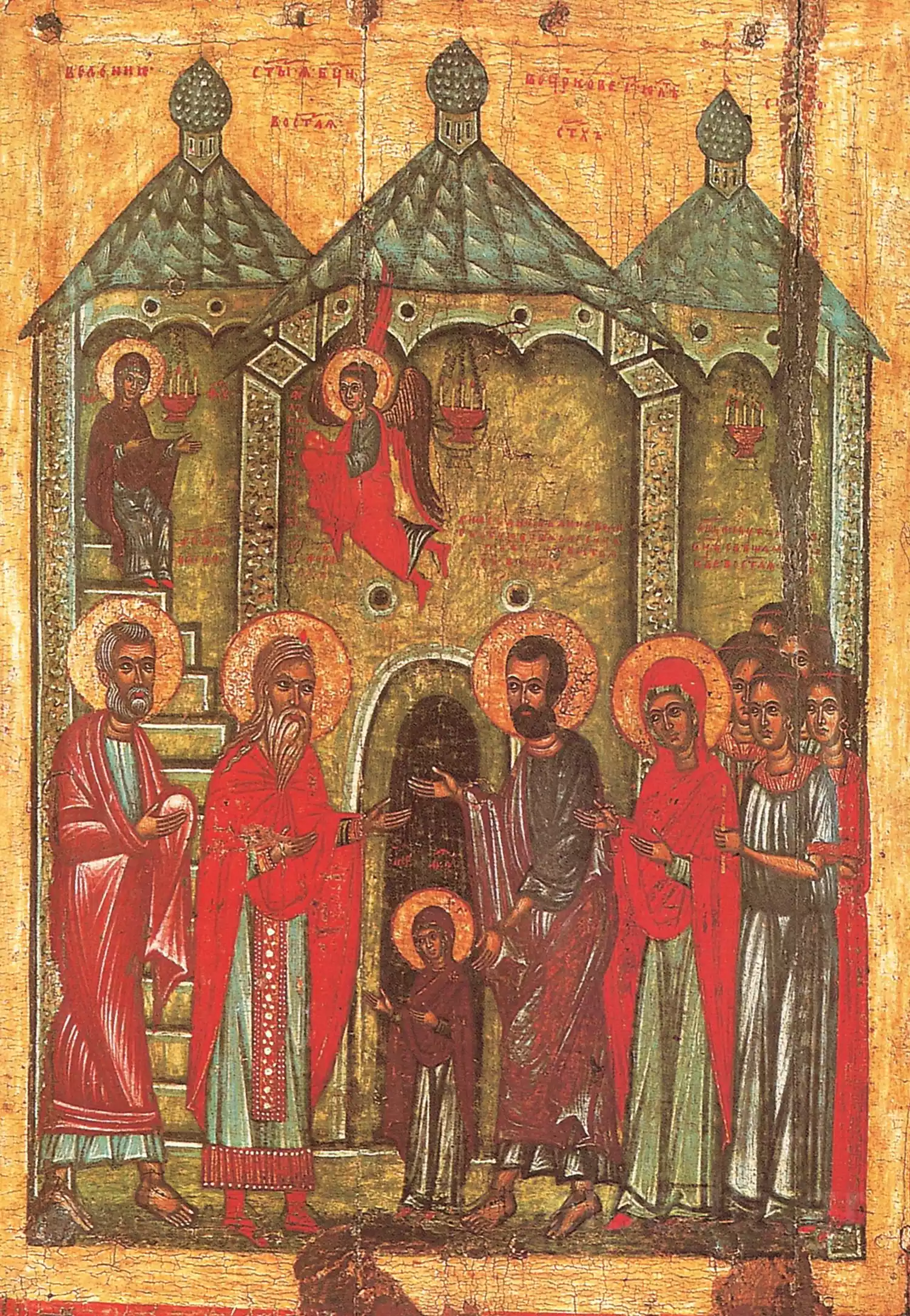

Standing before this wooden icon, one can’t help but wonder. What exactly are we seeing? Are these merely colors? Is it the story of a technique that has been lost, or perhaps a human endeavor to grasp the intangible? The 14th-century icon of the Presentation of the Virgin Mary housed in the Russian Museum is no ordinary object. It carries the chill of the North and the flame of a faith that knew no compromises. Gazing at it, the first sensation is a strange calmness, an order that seems to come from another realm. It is not the naturalistic representation we are accustomed to in the West. Here, things are different. More austere. More introspective.

Perhaps the artist, whose name remains unknown to us, did not aim to depict a girl climbing stairs. Instead, he sought to illustrate the passage. The transition from the world of decay to the realm of the sacred. And he does so in a way that surprises you. With colors that shout and shapes that remain silent. The Northern School, this unique artistic expression that flourished far from major centers, has its own logic. A logic that strips away the unnecessary. That retains the essence. Just as the theological thought of the time sought to find God not in many words but in the experience of community.

And here lies the intrigue. In how art becomes a vessel of meaning without being verbose. We see the composition and feel that something is missing. Perhaps perspective? Perhaps realism? No. What is absent is the noise. Everything is arranged with a wisdom that is unsettling. The figures do not merely rest on the ground; they seem to float in a spiritual space where the laws of gravity have been abolished or rather replaced by other, spiritual laws.

While the eye attempts to grasp the details, the mind travels back to the era. To that 14th century filled with turmoil yet also abundant in light. There is a strong academic interest in how these forms traveled, how ideas moved from Byzantium to the frozen North, and how there, amidst isolation and harsh climate, they transformed into something new. Something that is no longer a copy but an original creation. A cry of silence.

The Artistic Language of the North and the Function of Space

I wonder if we have ever truly appreciated the boldness of these painters. We tend to judge them by the standards of the Renaissance, and in doing so, we miss the point. We lose the essence. This particular image is a lesson in freedom. Observe the buildings in the background. They are not houses. They are not temples in the sense of architectural stability. They are veils. They are the settings of a divine liturgy that is eternally performed. The painter is not concerned with showing us how temples were built in Jerusalem. He is completely indifferent to the historical accuracy of the structure. What drives him is theological truth. That the temple is the space where man meets the divine.

The Geometry of Encounter and the Colors of Silence

And how does he convey this? Through colors. Primarily with the dominant red and earthy ochre. These are not decorative elements. They are statements of identity. The red of the fabric that connects the buildings, the so-called velum, is not just a piece of cloth. It indicates that what we see occurs in an interior space, yet simultaneously in a realm that transcends us. The geometry of the composition is strict. Almost musical.

Let’s closely examine the movement. There is a flow from left to right. A procession. The parents, Joachim and Anna, follow but do not push. They stand with a certain humility. How human and how divine at once. To hand over your child and know that they no longer belong to you. The figure of the Virgin Mary, small in size yet mature in posture, is the center of the world at this moment. She is not a stumbling infant. She is a determined being. She wears her mantle in a way that foreshadows her future. Her gaze does not look back. It looks only forward, towards Zacharias, towards her destiny.

And here comes the great “crack” in our logic. How can a three-year-old child possess such maturity? The painter winks at us. He tells us, do not look at the age of the body. Look at the age of the soul. The 14th-century icon of the Presentation of the Virgin Mary from the Northern School does not conduct a psychological analysis in the modern sense. It performs an ontological incision. It shows us the face not as it appears, but as it is in the perspective of eternity.

The architectural depth, with its tall towers and openings, seems to constrict the forms yet also protect them. It is as if the space participates in the mystery. It is not a dead background. It breathes. The buildings lean slightly, obeying an internal rhythm, a reverse perspective that brings the subject closer to the viewer rather than distancing it. It invites us to enter. To become part of the procession.

![]()

The Dance of the Virgins and the Community of Faces

Behind the central scene, there is that group of girls. The torchbearers. If one pays attention, they will see that they are not separate units. They are a body. A community. Their faces resemble each other, their movements are almost identical. Yet, they are not a mass. They are a society. They hold the torches not to illuminate – the light in the image does not come from the torches, it comes from everywhere – but to honor.

This detail is striking when you think about it. In our time, where individuality has become a banner and each of us lives enclosed in the shell of our ego, this image presents an alternative way of life. The common journey. No one is saved alone. Not even the Virgin Mary goes to the temple alone. She is accompanied. The joy of the celebration is a collective affair.

The garments of the girls, with their folds falling vertically, create a rhythm reminiscent of a colonnade. They visually support the composition. If you were to remove them, the image would collapse. It would lose its balance. This sense of measure, of harmony that does not shout, is characteristic of great art. The painter does not attempt to impress with intricate patterns on the clothing. He uses simple lines, pure colors. As if to say that beauty lies in simplicity. In abstraction.

And Zacharias. Bowed, with respect, he welcomes the little girl. The relationship of their hands tells the whole story. A touch that is not a grasp, but acceptance. The priest, representative of the old law, welcomes the Ark of the new covenant. There is a tension here. A silent conversation of generations. The old that ages and the new that comes to renew the world.

I often wonder, when viewing such works, how far we have strayed from this direct language. We search for meanings in complex analyses and miss the obvious that is right before our eyes. This art was not created to adorn museum walls. It was made to function. To speak to people who suffered, who hoped, who believed. The wear of time on the surface of the wood, the cracks, the fading in certain areas, all these do not diminish its value. On the contrary, they add to it. They are the marks of human history that touch the sacred.

The use of space in the icon at the Russian Museum, with its bold shaping, shows us that the Northern School was not a provincial attempt at imitation. It was a dynamic interpretation. These artists had the courage to see the world with their own eyes. To see the light through the prism of their own spirituality. And this light, even today, centuries later, has the power to move us. To momentarily halt us from the frantic pace of daily life and whisper something about a lost truth. About a community of faces that perhaps, I say perhaps, is still achievable.

Because ultimately, what is this image? A window. And it is up to us whether we keep it closed or open it to let in some fresh air into the room of our existence.