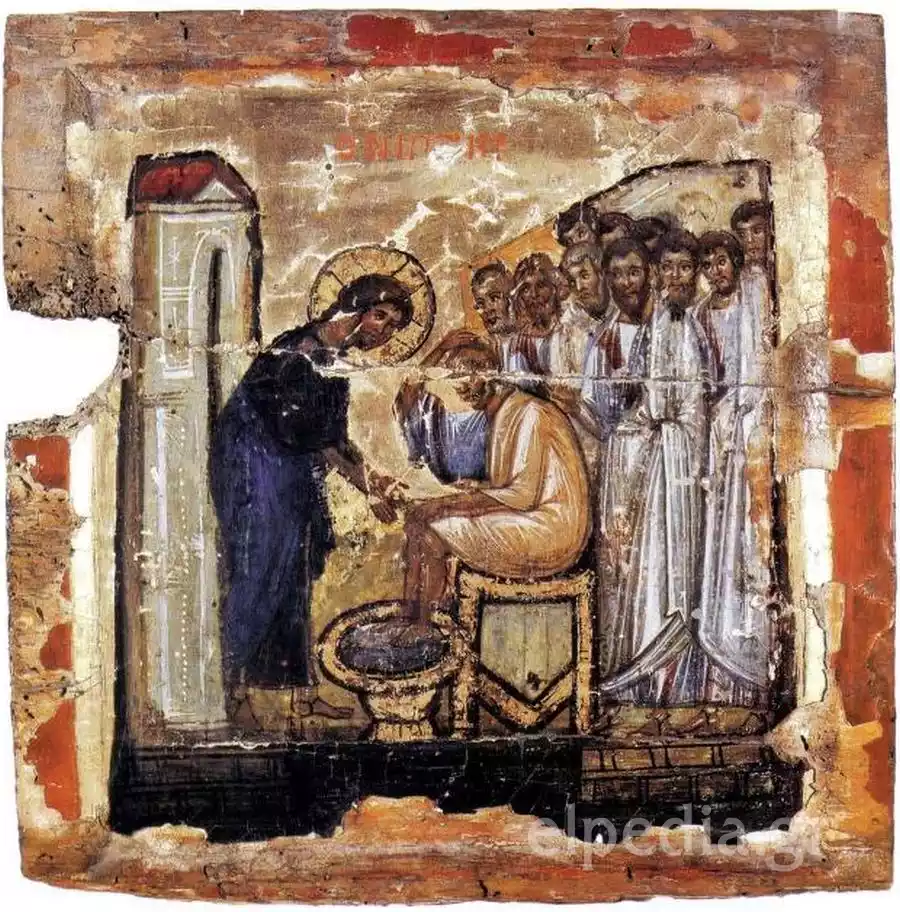

Before a work of such density, almost square, with dimensions of 25.6 x 25.9 centimetres, guarded like the apple of one’s eye in the Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sinai, words are almost superfluous. We are speaking, of course, of the icon of the Niptir, the Washing of the Feet, a masterpiece crafted upon wood, which the specialists place, and not without reason, in the first half of the 10th century. The scene, naturally, is well-known: Jesus, in an act of ultimate humility, stoops to wash the feet of Peter, while at the same moment the other disciples watch, crowded together, almost speechless. This is not merely a hagiography; it is a theological commentary, a historical testimony that condenses, in a manner almost instantaneous, the aesthetic and spiritual quests of an entire era. Its illusionistic style, its dramatic tension, and its probable function as part of a templon epistyle, perhaps the most ancient surviving example with scenes from the Dodecaorton (Spingou), render it an object of study that is not easily exhausted. It is a window, one might say, into an art that was not afraid to be at once profoundly human and utterly transcendent. My first encounter with this icon, even through reproductions, left a feeling of awe for the economy of means and the narrative power that such a small surface can conceal.

A Composition of Humble Divinity: Iconographic Keys

One looks at the icon and is submerged. On the left, the figure of Christ, dominant despite its humble posture, is clad in dark, almost black garments, creating a violent, silent contrast with the light-coloured, luminous vestments of the disciples. This choice in colour, it is not accidental, never is it accidental in Byzantine painting. It is a declaration; the declaration of the divine nature that “empties itself,” that self-humiliates in order to serve man. Peter, seated, his feet already inside the basin, brings his right hand to his head in a gesture almost instinctive, a gesture that is the visual translation of his evangelical utterance: “Lord, not my feet only, but also my hands and my head” (John 13:9). A cry of wonder and awe. Behind him, the other disciples, a compact, indivisible group with common faces, almost standardised, with intense features and canted noses, stand upright. They are watching. They do not participate actively, but their presence is catalytic, defining the space and time of the sacred moment, which is set “in an upper room” through the simple, architectural indication of the low wall in the background. The study of Byzantine iconography (Folda) reveals how every detail here is not decorative, but functions as a carrier of a deeper meaning, transforming the simple representation into a complex theological treatise.

The Hand of the Master: Style, Date, and the Epistyle Question

How can you be certain about a dating? You can never be, not absolutely. However, the style of this icon, what scholars call “illusionistic,” cries out for the first half of the 10th century, for the period of the Macedonian Renaissance. There is a plasticity in the figures, an attempt to render volume, and a sense of space that alludes to classical models, filtered, however, through Byzantine spirituality. The folds of the garments are not mere lines, but seem to genuinely envelop real bodies, while the light and shadow, though spare, provide a sense of depth. Another element, perhaps more decisive, is the posture of the Apostles. Here, all stand erect, observers of the scene. From the 11th century onwards, the iconography of the Niptir changes, it becomes enriched… many of the disciples begin to be depicted seated, untying their sandals, in a more “earthly,” preparatory act. The absence of this motif from the Sinai icon is strong evidence of its antiquity. And then there is the object itself: square, with the grain of the wood running horizontally. This is no accident. It suggests that this is not an autonomous, portable icon, but part of a larger composition, a templon epistyle. If this hypothesis holds, then we do not simply have an important icon, but the most ancient known example of a Dodecaorton epistyle, a discovery that reshuffles our knowledge of Byzantine Art (Lymberopoulou and Duits) and the evolution of liturgical art.

What remains in the end? A small wooden surface, worn by time, silent, enclosed in the monastery of Sinai. And yet, within these few square centimetres, an entire world is condensed. The icon of the Niptir is not just a “historical artefact” or a “work of art.” It is a living theology, an act of faith rendered in colour and light, a bridge that connects us to the aesthetic and spiritual universe of the 10th century. Its significance, as the most probable earliest example of an epistyle icon, is immense for the history of art, but its true power lies elsewhere. It lies in its ability to transcend time and to speak directly to the human conscience about humility, service, and divine love. It is one of those rare Byzantine icons (Folda) that, no matter how much you analyse it, something will always escape you…

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is the Byzantine icon of the Washing of the Feet from Sinai so significant?

Its significance lies in its great age, being dated to the first half of the 10th century, and its remarkable illusionistic style. Furthermore, its square shape and the horizontal grain of the wood strongly suggest it is the earliest surviving part of a templon epistyle depicting the Dodecaorton, making it a unique artefact for understanding the evolution of Byzantine art.

What does the gesture of the Apostle Peter symbolise in this Sinai icon?

The gesture of the Apostle Peter, raising his hand to his head, is a direct visual reference to his dialogue with Christ as recorded in the Gospel of John. It symbolises his initial refusal followed by awe and total acceptance, asking the Lord to wash not only his feet but his entire being, body and soul.

How is this Byzantine icon of the Washing of the Feet dated?

The dating of this icon to the first half of the 10th century is based primarily on stylistic criteria. The illusionistic rendering, with its sense of volume and depth, is characteristic of the Macedonian Renaissance. Moreover, the iconographic detail of all the apostles standing upright, unlike in later depictions, reinforces the argument for an early date for this Sinai work.

What was the likely original function of the Sinai icon of the Niptir?

Due to its square shape and the horizontal orientation of the wood grain, scholars posit with a high degree of certainty that the icon was not a standalone piece. It most likely formed part of a templon epistyle, the horizontal beam above the chancel barrier, upon which the principal scenes from the life of Christ, the so-called Dodecaorton, were depicted.

How does this depiction of the Washing of the Feet differ from later Byzantine icons?

The primary difference is found in the composition of the group of apostles. In this early 10th-century icon from the Sinai Monastery, all disciples are shown standing, as passive witnesses to the sacred act. In contrast, from the 11th century onwards, the custom of depicting some apostles seated while removing their sandals becomes prevalent, lending the scene a more narrative and human character.

Bibliography

- Folda, Jaroslav. Byzantine Art and Italian Panel Painting. 2015.

- Folda, Jaroslav. Crader Art in the Holy Land, From the Third Crusade to the…. 2005.

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki, and Rembrandt Duits. Byzantine Art and Renaissance Europe. 2013.

- Spingou, Foteini. Sources for Byzantine Art History: Volume 3, The Visual…. 2022.