Amphora from 750 BC in Athens depicts a woman’s mourning, offering unique historical value and aesthetics.

The Geometric period, dated to the 9th and 8th centuries BC, is not merely a precursor to classical art but an independent and captivating artistic expression that marks the rebirth of the Greek world after the so-called Dark Ages. It is the time when art, primarily through pottery, moves away from simplicity and begins to “speak” with a new, strict vocabulary based on logic, order, and geometry. These vessels, which we now study as valuable historical documents, capture a society’s effort to redefine itself, organize its world, and ultimately tell its stories. The study of the evolution of pottery from this period (Cook) allows us to trace step by step the formation of the artistic idiom that would serve as the foundation for the entire subsequent history of ancient Greek art (Stansbury-O’Donnell). These objects are not merely decorative vessels; they are the silent witnesses to the birth of a civilization.

The Emergence of a New Order: From Shapes to Narratives

The Proto-Geometric period had already introduced the use of the fast wheel and compass, but artists limited decoration to specific areas of the vessel. However, the Geometric era brought about a radical change. A change that was visible everywhere. Soon, an almost obsessive trend for complete decoration, known as horror vacui (the fear of emptiness), prevailed, covering the entire surface of the vessels with dense, repetitive patterns. Meanders, triangles, curved lines, and concentric circles, organized into strict horizontal bands separated by triple lines, created an effect that impresses with its precision and discipline, an aesthetic that seems directly linked to Art and Geometry as fundamental principles (Ivins Jr). But why this absolute dominance of abstraction? Perhaps the answer lies in the very sources of inspiration for the artists, as many of these patterns strongly resemble weaving and basketry, crafts traditionally practiced by women, raising the intriguing question of the potential leading role of women in shaping this early aesthetic.

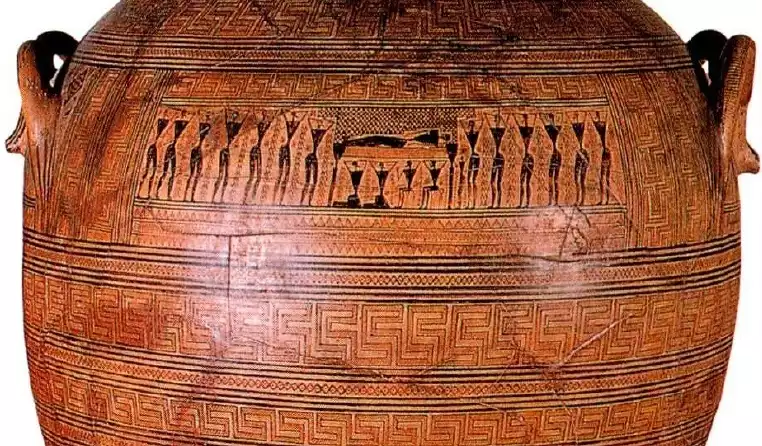

As the 8th century progressed, a transformative change occurred. Within the strict framework of geometric shapes, the first forms began to timidly appear. Initially, they were isolated animals, birds, or horses, incorporated as another decorative element within a band. Shortly thereafter, these figures began to repeat rhythmically, creating friezes. The decisive step, however, was the introduction of the human form, marking the beginning of narrative art, as noted in J. Carter’s relevant study. This evolution culminated in the middle of the century with the monumental funerary vessels of the Dipylon, kraters and amphorae of enormous dimensions that served as markers in the graves of Athenian aristocracy. Here, human figures, although rendered schematically—with triangular torsos, dot-like heads, and linear limbs—now participate in complex scenes, primarily the prothesis (the display of the deceased) and the ekphora (the transport to burial), surrounded by mourning dancers expressing grief with their characteristic gestures. Action, emotion, and narrative had now definitively entered the repertoire of Greek art, reflecting a society that, like in the Homeric epics, showed a keen interest in human achievements, myths, and rituals, thus shaping the ancient perception of Greek art (Pollitt).

Dialogues with the East and the Dawn of a New Era

The development of geometric art did not occur in a cultural vacuum. On the contrary, the intensification of trade relations with the peoples of the Near East during the 8th century BC brought new ideas and patterns to the Greek world. Although vase painting was not particularly popular in the East, the influence is evident in other art forms and gradually in pottery. The appearance of lions, creatures unknown in Greece but dominant in Eastern art, on the vessels of the late geometric period, serves as the most eloquent harbinger of the new era that was dawning, the Orientalizing period. Scholars examining the Greek geometric pottery found in archaeological sites in the East (Francis & Vickers), as well as conducting chronological parallels with the pottery there (Medvedskaya), have demonstrated the bidirectional nature of these contacts.

It is likely that the very idea of developing an art focused on narrative with human and animal forms was inspired by Eastern models. But what was the reaction of Greek artists? The translation of these influences into the local artistic idiom was immediate, radical, and entirely creative. Greek artisans did not copy. They assimilated, filtered, and ultimately integrated foreign elements into a framework that was entirely their own, subjecting them to the structure, logic, and aesthetics they had already developed. The lion may have come from the East, but the form it took on an Attic krater was undeniably Greek. Alongside Athens, which led the way, significant local workshops developed throughout Greece, from Corinth and Argos to the Cyclades and Crete. Each workshop developed its own distinctive style, as evidenced by the findings, such as the geometric vessels from Volimidia (Coulson), creating a rich diversity attributed to both geographical factors and the demands of local markets. As the period approached its end around 700 BC, the strict geometric outline began to loosen, forms acquired more curves and internal details, and complex decorative patterns receded, making way for larger, more legible narrative scenes, thus paving the way for the Orientalizing and ultimately the Archaic art.

Geometric krater with zigzag patterns and horse figures, height 57 cm.

The Legacy of Lines: Geometric Art as a Cornerstone

Thus, as the 8th century drew to a close, the strict, almost mathematical language of geometric art began to transform. It was not a sudden rupture. It was a gradual, almost organic evolution, a relaxation of the constraints that had imposed absolute order for nearly two centuries. The intricate geometric patterns that once flooded every inch of the surface began to recede, now yielding the leading role to narrative scenes, which became increasingly ambitious, more complex, and more legible. How can we interpret this transition? It is not the decline of a style but its maturation, the moment when the discipline it imposed gave way to the expressive freedom that it had itself made possible, laying the groundwork for the entire subsequent Greek pottery (Cook). The influx of exotic creatures from the East, such as sphinxes, griffins, and sirens, did not undermine Greek art; rather, it enriched it, providing a new vocabulary of imagination for artisans who, having now mastered the art of spatial organization and narrative, were ready to tell even more captivating stories.

This obsession with narrative, which peaked at the end of the Geometric period, was not a random aesthetic choice but a profound reflection of the monumental social and political changes sweeping the Greek world. It was the era of the birth of the city-state, the polis, a new way of organizing collective life that demanded new means of expressing collective identity. At the same time, the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, were crystallizing into written form, offering a pan-Hellenic body of myths, heroes, and values that united the scattered Greek communities. Geometric vessels, therefore, transformed into a visual canvas upon which these very stories were projected, making them visible and comprehensible to all. A battle scene on a krater did not merely depict any conflict; it echoed the heroic battles of the Trojan War, while the depiction of a sea voyage could evoke the adventures of Odysseus. Art became the medium for disseminating and embedding a shared cultural heritage, a mirror in which the emerging Greek society could see and admire itself. The human form, although still schematic, was now acquiring a leading role, not merely as a decorative element but as the main bearer of meaning, drama, and pathos.

The geometric aesthetic, however, did not confine itself to the surface of clay vessels. It permeated every aspect of material culture, revealing a mindset deeply rooted in a love for order, symmetry, and structure. In the cast bronze figurines of the era, the forms of warriors, charioteers, and horses are rendered with the same angular abstraction that characterizes their painted counterparts. The monumental bronze tripods, which served as valuable offerings at the great pan-Hellenic sanctuaries of Olympia and Delphi, are adorned with intricate geometric designs engraved on their surfaces. Even in humble, everyday objects, such as the brooches (fibulae) that held garments, the geometric spirit is omnipresent. This diffusion of style demonstrates that it was not merely an artistic technique but a way of thinking, an effort to impose order upon chaos. It was the visual expression of the same logic that would later lead to the birth of philosophy and science, a deep belief that the universe is governed by principles and rules that can be understood and represented.

In conclusion, the Geometric period was not simply a preparatory or “primitive” phase of Greek art. It was the fundamental, absolutely necessary matrix from which all subsequent achievements emerged. It was the strict school that taught the Greek artist the essential principles of composition, structure, and narrative. The discipline of line and the logic of shape did not restrict creativity; rather, they liberated it, providing a solid framework upon which it could build. Without the mastery of spatial organization into zones and metopes, the complexity of the compositions of black-figure and red-figure vase painting would be unimaginable. Without the bold introduction of the human form at the center of artistic interest, the anthropocentric art of the classical period, with its idealized depiction of the human body, would never have been born. The Geometric period, therefore, bequeathed to the following centuries not a set of shapes but a way of seeing the world: organized, rich in meaning, and centered on humanity. It was the silent yet resounding declaration of the beginning of a civilization that would forever change the course of human history.

Bibliography

Carter, J. (1972), ‘The beginning of narrative art in the Greek Geometric period’, Annual of the British School at Athens, 67, pp. 25-58.

Cook, R.M. (2013), Greek painted pottery. London: Routledge.

Coulson, W.D.E. (1988), ‘Geometric pottery from Volimidia’, American Journal of Archaeology, 92(1), pp. 53-74.

Francis, E.D., and Vickers, M. (1985), ‘Greek Geometric pottery at Hama and its implications for Near Eastern chronology’, Levant, 17(1), pp. 131-138.

Ivins Jr, W.M. (1946), Art & geometry: a study in space intuitions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Medvedskaya, I.N. (1986), ‘A study on the chronological parallels between the Greek Geometric style and Sialk B painted pottery’, Iranica Antiqua, 21, pp. 57-93.

Pollitt, J.J. (1974), The Ancient View of Greek Art. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Stansbury-O’Donnell, M.D. (2015), A history of Greek Art. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.