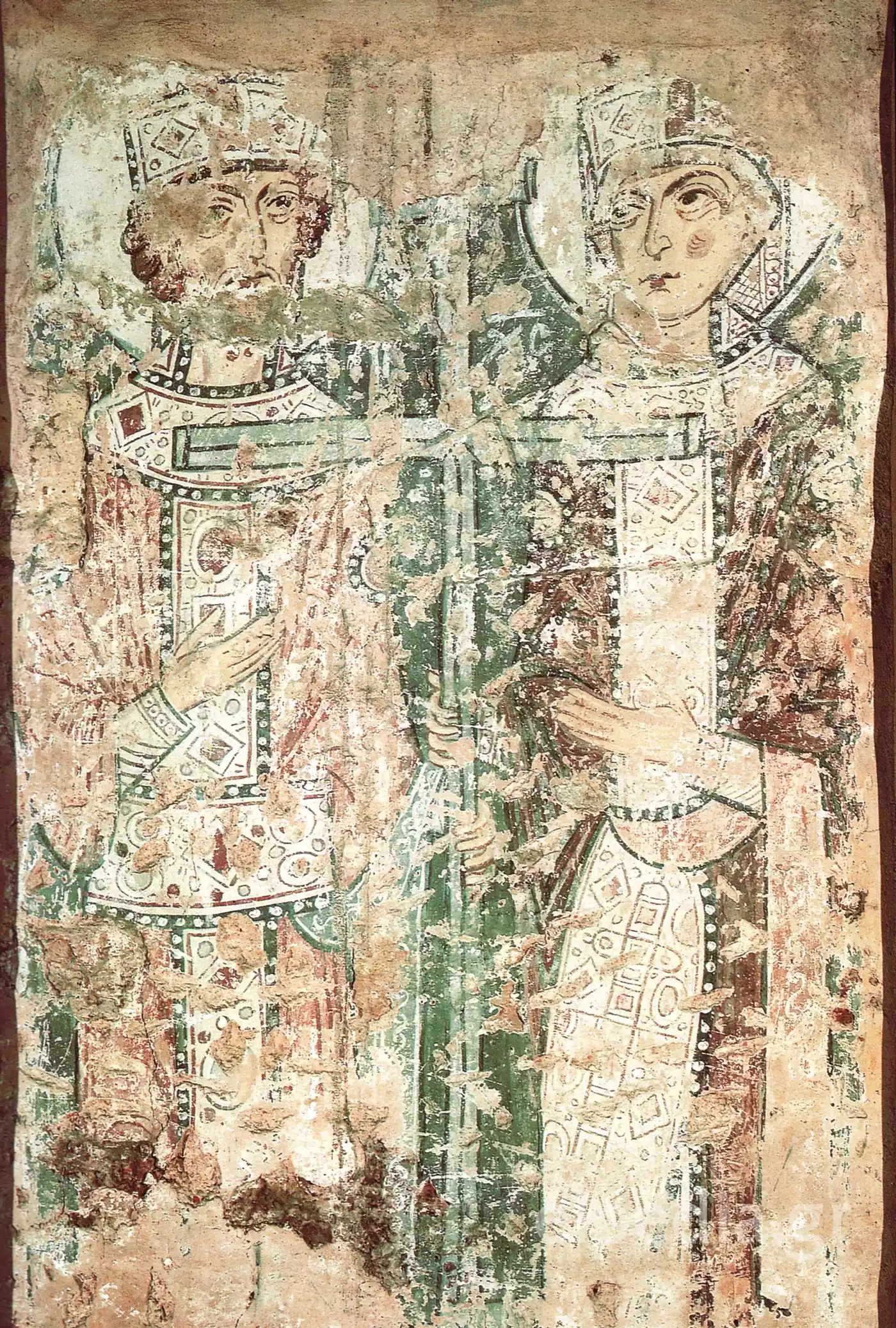

The fresco of Saints Constantine and Helen (12th century) in the Cathedral of St. Sophia in Novgorod, a powerful symbol of the transfer of Byzantine power.

These figures are not exactly present here. They float, one might say, on a wall that has long forgotten its original appearance, ghosts of an empire that survived through such ephemeral images, transported miles away from its homeland. We are confronted with a 12th-century fresco, one of the many layers of history that cover the walls of the Cathedral of St. Sophia in Novgorod, Russia. It depicts Emperor Constantine and his mother, Saint Helen, holding the Holy Cross. The wear is evident, almost painful – the plaster has cracked, the colors have faded, the faces have lost their features, yet their priestly posture, absolute frontal presence, and imposing aura remain almost unchanged, a stubborn testament to an era that sought to establish its own identity by borrowing symbols from another, older, and more powerful one. The question is not so much theological as it is political: why these two, and why here, in this northern outpost of the emerging world of the Rus? The answer lies in the very need for legitimization, in the transfer of a model of power that directly connects earthly hegemony with divine approval, a fundamental principle for the dynastic ideology of the Rus (Simmons).

The Material Reality of an Imperial Idea

One must momentarily set aside the religious dimension to see what is truly happening here. What we are witnessing is not a mere icon but a political manifesto captured in wet plaster. It is the very texture of history, the effort of a new power to don the mantle of Roman and Byzantine heritage. The choice of figures, Constantine and Helen, is far from random for the history of Novgorod, a city-state seeking models of prestige and stability.

A Glance at the Worn Plaster

Let us approach the wall. The technique is that of fresco, al fresco, which requires speed and certainty, as the paint must be applied while the plaster is still wet. The outlines are bold, almost harsh, defining the figures with a certainty that stands in stark contrast to their current fragmented state. The garments are imperial, intricate, filled with geometric patterns and imitations of precious stones. It is the Byzantine loros, the ceremonial garment symbolizing the emperor’s supreme authority in Constantinople. Here, in the cold climate of Novgorod, this garment is not merely clothing; it is a statement. It is the visual embodiment of an entire worldview, a kind of political advertisement that proclaims: “We too are heirs to this great tradition.” The very iconography of Novgorod, as related research has shown, is characterized by an archaizing solidity, a rejection of classical grace in favor of monumental assertion (Kriza). The figures do not so much look at you as compel you to recognize them.

The Cross as a Political Emblem, Not (Only) Religious

And then, there is the cross. Positioned right at the center of the composition, between the two figures, it serves as a visual and ideological axis. It is not merely the symbol of Christian faith. It is, primarily, the trophy of Constantine’s victory at the Milvian Bridge, the emblem that transformed a marginal religion into state ideology. Helen, with the discovery of the True Cross in Jerusalem, imparts to this military trophy the necessary sanctity and authenticity. By holding it together, mother and son do not merely display their piety; they establish a dynasty that derives its legitimacy directly from God through this specific object. This very tradition for Constantine and the divine origin of his power made it so appealing to the rulers of Novgorod (Плюханова). Thus, this fresco acts as a mirror, where local lords could see their own power elevated and sanctified, connected to the inception of the Christian empire. And so, the message is delivered.

A Message on the Wall: The Audience and Context

For whom, then, was this austere and somewhat otherworldly spectacle intended? Certainly not for the simple, illiterate believer seeking comfort. Its placement within the cathedral—likely near an entrance or in a chapel, such as the Martyr’s aisle, a passage for officials—suggests a more targeted audience. This image spoke to princes, bishops, boyars, to those who understood the language of power and recognized the value of the Byzantine seal. It was a constant reminder of the source of their own authority, a way for them to see themselves as continuators of a sacred, imperial plan that had begun centuries earlier, on the banks of the Tiber and the Bosporus, and now found a new, unexpected homeland on the banks of the Volkhov River.

The “Translated” Empire

What we see here, ultimately, is not a simple copy. It is an act of cultural and political translation. The Eastern Orthodoxy provided the ideological framework, and Byzantine images the visual vocabulary (Grishin). However, this language, when spoken with a Russian accent, takes on a different tone. The subtlety and refinement of late Comnenian art, found in Constantinople, here give way to a rougher, more direct, and uncompromising statement of power. It is an empire adapted to the needs of the frontier, less theologically complex, but absolutely clear in its political message. The overall program of the frescoes in the cathedral functioned as a well-organized discourse, where each image had its place and role in building this new world (Царевская).

The Endurance of the Shadow

Looking again at these two worn figures, one cannot help but think of the irony. They were created to project an idea of eternal, divinely ordained power, yet their material existence has proven so fragile. The plaster cracks, the colors fade, the faces become unrecognizable. And yet, the shadow of the idea they carry remains. The fresco has survived fires, wars, revolutions, centuries of neglect, and moments of recognition. Perhaps its true strength was never in its bright colors or precious materials, but in this very ability of images to convey abstract concepts of power across time and space. The material body of the empire fades, but its ghost—somehow, it continues to gaze at us from the wall.

Bibliography

ГОРДИЕНКО, Э, ‘The Light of Novgorod’s Sophia’, Rodina, 2007.

Grishin, A., ‘Eastern Orthodox’, in The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity, 2007.

Kriza, Á., Depicting Orthodoxy in the Russian Middle Ages: The Novgorod Icon of Sophia, the Divine Wisdom, 2022.

Παπαϊωάννου, Κ., Byzantine and Russian Painting, trans. El. Nakou, Alternative Editions, 2007.

ПЛЮХАНОВА, М.Б., ‘The Church Tradition about Constantine, Helen, and the Elevation of the Cross in the Church Life and Literature of Ancient Novgorod’, Constantinople as the Center of Civilization, 1998.

РЕНЁВ, В.В., ‘THE CONCEPT OF THE PAINTINGS OF THE ALEXANDER NEVSKY CATHEDRAL IN NIZHNY NOVGOROD’, ICON IN RUSSIAN LITERATURE AND CULTURE.

РУДЁНОК, А.Е., М.Н. Землянко, and Д.А. Кузьбар, ‘JOURNEY TO GREAT NOVGOROD’, VI Masharov Readings, 2012.

Simmons, S.C., ‘Rus’ Dynastic Ideology in the Frescoes of the South Chapels in St. Sophia, Kiev’, in From Constantinople to the Frontier: The City and the …, 2016.

ЦАРЕВСКАЯ, Т., ‘Themes of the Exaltation of the Cross and Great Saturday in the Program of the Painting of the Church of Theodore Stratilates in Novgorod’, Art Studies, 2008.