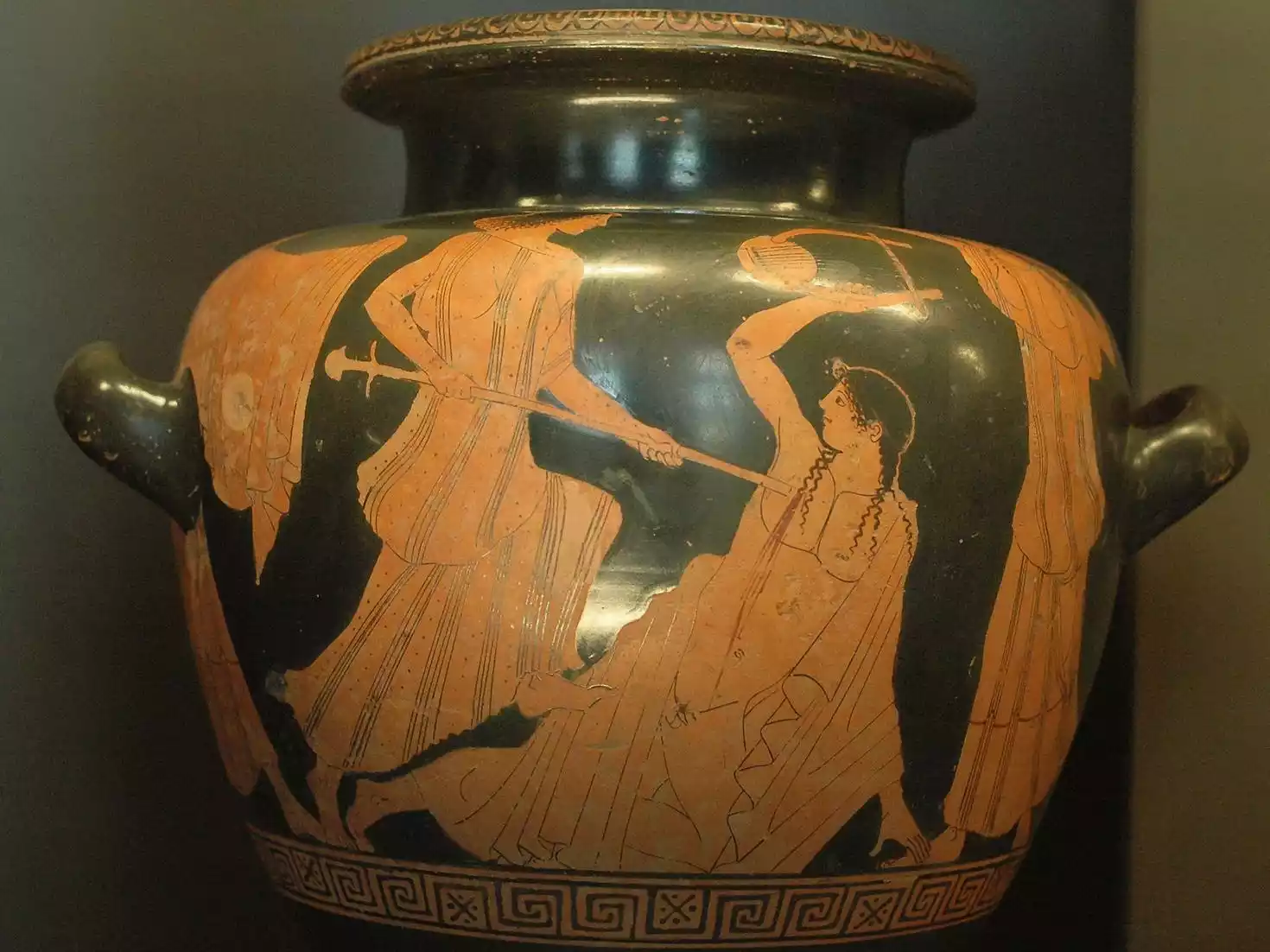

The Death of Orpheus. Attic red-figure stamnos by Hermonax, ca. 470 BC. Related to the Orphic Mysteries. Louvre Museum (G 416).

In the rich world of ancient Greek religion, beyond the worship of the Olympian gods, there existed what were known as “mysteries,” unique religious practices that promised initiates deeper knowledge and often a better fate after death. Among these mystery cults, the Orphic Mysteries hold a special place, a set of beliefs and rituals intricately linked to the legendary figure of Orpheus. Orpheus, the son of the Muse Calliope and, according to one version, the god Apollo, was the mythical musician and poet whose lyre enchanted gods, humans, and all of nature, even capable of moving the deities of the Underworld.

The Orphic Mysteries differ from other cults as they introduced a distinct theology and cosmogony, with their own myths about the creation of the world and the origins of gods and humans. At the core of their teachings was the belief in the immortality of the soul, its fall into the material world due to a primordial sin (linked to the myth of Dionysus Zagreus and the Titans), and the need for purification and liberation through a specific way of life (the so-called “Orphic life”) and secret rituals. These ideas had a significant impact on the philosophy and religious thought of the ancient Greeks, offering an alternative perspective on life, death, and the universe, with the Orphic teachings discussed alongside esoteric texts (Dimopoulos). The allure of these mysteries lies precisely in the promise of revealing sacred truths, accessible only to the initiated, and the hope for a more favorable afterlife. (It may be worth exploring more about the ‘Orphic Life’).

The Myth of Orpheus: The Musician Who Enchanted the Underworld

The figure of Orpheus is central to understanding the eponymous mysteries. Son of the Muse Calliope and, according to some traditions, of the god Apollo or the Thracian king Oeagrus, Orpheus was considered the greatest musician and poet of antiquity. His music, played on the lyre (a gift from Apollo), was so enchanting that it could tame wild beasts, move rocks and trees, and even captivate the gods. His fame led him to join the Argonauts, where his singing intervened heroically in critical moments, for instance, covering the dangerous song of the Sirens.

The most famous story associated with Orpheus is his tragic love for the nymph Eurydice. Shortly after their wedding, Eurydice was fatally bitten by a snake. Heartbroken, Orpheus made the bold decision to descend to Hades to bring her back. With his music, he managed to move Charon, Cerberus, and ultimately Pluto and Persephone, the rulers of the Underworld. They agreed to allow him to take Eurydice back to the world of the living, on one condition: he must not look back at her until they both reached the sunlight. As they ascended, just before the exit, anxiety and doubt overwhelmed Orpheus. He turned to see if his beloved was following him, only to see her fade away into the shadows forever. This moment, where Orpheus found himself beside her just as Eurydice was lost, encapsulates the ultimate tragedy of the myth (Fry). After the irrevocable loss of Eurydice, Orpheus wandered despondently, avoiding the company of other women. His death is also shrouded in myth, with the most prevalent version stating that he was torn apart by frenzied Maenads (followers of Dionysus) in Thrace, either because he scorned them or because he did not honor Dionysus.

Orpheus among the Thracians. Attic red-figure bell krater, ca. 440 BC.

Key Teachings of Orphism: Soul, Purification, and Immortality

The Orphic Mysteries offered a distinct belief system focused on the fate of the human soul. At the heart of Orphic teaching was the idea of dualism: the perception that humans consist of two elements, a divine and immortal one (the soul) and a mortal and material one (the body). The soul, of divine origin, was considered trapped or “imprisoned” within the body (the famous phrase “sōma sēma,” meaning the body is a tomb), as a result of a primordial sin.

This primordial sin is linked to the central Orphic myth of Dionysus Zagreus. According to this myth, the Titans, out of envy, dismembered and consumed the young Dionysus, son of Zeus. Zeus, enraged, struck them down. From the ashes of the Titans, which contained the remnants of the divine Dionysus, humanity was created. Thus, humans carry within them a dual nature: the titanic, material, and sinful, and the Dionysian, divine, and immortal. The goal of Orphic initiation and the “Orphic life” was to purify oneself from the titanic element and liberate the divine soul.

This liberation could not be achieved in a single lifetime. Orphism introduced, or at least widely disseminated, the idea of reincarnation (or palingenesis), the successive embodiment of the soul in different bodies until complete purification was achieved. To expedite this process, the Orphics followed a strict way of life that included moral codes, ritual purity, and, most importantly, abstaining from the consumption of sentient beings (vegetarianism), as they believed that animals could also host souls in the process of reincarnation. Through initiation rituals and adherence to these rules, the believer hoped to break the cycle of births and return the soul to its divine state (Kakridis).

The violent murder of Orpheus by the Maenads, in a drawing by Albrecht Dürer (1494). This myth is a central element of the Orphic Mysteries tradition. Kunsthalle, Hamburg.

The Orphic Cosmogony: An Alternative Creation Narrative

Beyond the teachings about the soul, Orphism developed its own distinct cosmogony and theogony, that is, its own narratives about the creation of the universe and the genesis of the gods. These narratives, preserved mainly through hymns and references from later authors (such as the Neoplatonists), present a picture quite different from the more well-known version of Hesiod’s Theogony.

At the beginning of all things, according to many Orphic sources, there was not Chaos, but the eternal Time (often depicted as winged and with animal heads) and his companion, Necessity. From their union, or from the primordial Night, the cosmic Silver Egg emerged. From this egg, the first creative deity, Phanes (meaning “he who reveals” or “shines”), was born, a hermaphroditic, winged entity with golden wings, often identified with Love, the Primordial, or Metis. Phanes contained within him the seeds of all beings and was considered the creator of heaven and earth.

The continuation of the Orphic theogony includes the succession of divine generations (Night, Heaven, Cronus), but with a critical intervention: Zeus, to gain absolute dominion, swallows Phanes, thus incorporating his creative power. Then, Zeus recreates the world and becomes the new beginning of all things. In this context, the birth of Dionysus-Zagreus from Zeus and Persephone is also included, who was destined to become the new ruler of the universe before his tragic dismemberment by the Titans. This complex and symbolic cosmogony emphasized the divine origin of the world and the soul, providing the mythological background for the Orphic teachings on purification and liberation.

Thracian woman, possibly from a scene of the death of Orpheus (a theme related to the Orphic Mysteries). Attic red-figure kylix, ca. 480–470 BC. Attributed to the Brygos Painter. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Rituals of the Orphic Mysteries: Initiation and Sacred Texts

As their name suggests, the Orphic Mysteries included secret initiation rituals, the details of which remain largely unknown, as initiates were bound by an oath of silence. However, from various sources and archaeological findings, we can form a picture of the nature of these rituals. Emphasis was placed on purity, both moral and physical. Prospective initiates likely underwent periods of fasting, abstinence, and purifying baths.

Central to Orphic worship were the sacred texts attributed to Orpheus himself. These included hymns, theogonical and cosmogonical poems (such as the so-called “Orphic Hymns”), and texts that described Orpheus’s descent into Hades or provided guidance for the soul’s journey after death. Understanding these texts, with their mysterious verses, was considered a privilege of the initiated and required special interpretation, accessible only after the performance of the secret rituals (Detienne). Some of these texts, such as the Derveni Papyrus (one of the oldest European “books”), offer a rare glimpse into the allegorical interpretation of Orphic poems by the followers of the cult.

Particularly significant are the findings of thin gold leaves (lamellae) that were placed in the graves of certain believers in areas such as Southern Italy, Thessaly, and Crete. These leaves bore engraved instructions for the soul of the deceased on how to navigate the Underworld, how to avoid dangers, and how to declare its Orphic identity to the chthonic deities (“I am a child of Earth and the starry Sky, but my lineage is celestial”), thus ensuring a favorable afterlife. These findings provide tangible evidence of the belief in the immortality of the soul and the importance of Orphic teachings for guiding the soul after death. (Archaeology continues to uncover elements of ancient mystery cults).

The Influence and Legacy of Orphism

Although Orphism was never a centrally organized religion with a priesthood and official temples like the Olympian worship, its ideas and practices had a profound and lasting impact on Greek thought and beyond. The emphasis on the immortality of the soul, moral living, purification, and the possibility of liberation from the cycle of incarnations resonated with many philosophers and religious thinkers.

Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans, seem to have shared many common beliefs with the Orphics, such as reincarnation, the need for an ascetic life, and vegetarianism. The relationship between Orphism and Pythagoreanism is complex and a subject of discussion among scholars, but the interaction is undeniable. Even more significant is the influence on Plato, who incorporated Orphic ideas (or ideas circulating in Orphic circles) into his central dialogues, such as “Phaedo,” “Gorgias,” and “The Republic.” Plato’s conception of the immortality of the soul, its imprisonment in the body, recollection, and the need for philosophical purification bears a clear imprint of the Orphic tradition.

Orphic ideas also permeated other mystery cults of antiquity, although they retained their own distinct character. The figure of Orpheus, the wise and tragic musician, continued to inspire poets, artists, and philosophers throughout the Roman era, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance, reaching into modern times. The quest for spiritual liberation, the belief in a hidden, divine spark within humanity, and the hope for transcendence over death—central themes in the Orphic Mysteries—remain timeless and continue to engage human thought. The legacy of Orphism is not exhausted in archaeological findings or philosophical references but lives on through the enduring fascination with the great questions of existence, the soul, and the afterlife.

Depiction of Orpheus enchanting Hades (1594), by Jan Brueghel the Elder. The descent into the Underworld is a central element of the myth behind the Orphic Mysteries. Oil on copper, Palazzo Pitti, Florence.

Different Interpretations & Critical Assessment

The study of the Orphic Mysteries is not without challenges and differing approaches. Scholars such as W.K.C. Guthrie emphasized the unity and continuity of the Orphic tradition, viewing Orphism as a distinct religious movement with specific roots and development. Others, like M.L. West, adopted a more critical stance, questioning the existence of a singular “Orphism” during the archaic and classical periods and seeing more a collection of disparate texts and ideas later attributed to Orpheus. Marcel Detienne focused more on analyzing the myths and rituals as cultural phenomena, examining the role of writing and interpretation in the Orphic tradition. The precise dating of Orphic texts and the historicity of Orpheus himself remain open issues, fueling ongoing academic discussion.

Conclusion

The Orphic Mysteries represent a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic chapter of ancient Greek religiosity. Offering a different perspective on the world, humanity, and the fate of the soul, they are distinguished by their profound philosophical implications and emphasis on individual spiritual quest and purification. The belief in immortality, the idea of reincarnation, the myth of Dionysus Zagreus, and the ascetic “Orphic life” composed a belief system that significantly influenced important thinkers and left its mark on the course of Western thought. Although many aspects of their rituals remain hidden behind a veil of mystery, the allure of Orpheus and the promise of his Mysteries for knowledge and liberation continue to attract us, reminding us of the eternal human quest for meaning beyond the confines of mortal existence.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly were the Orphic Mysteries in Greek Mythology?

The Orphic Mysteries were a set of secret religious beliefs and rituals of ancient Greece, attributed to the mythical Orpheus. They focused on the idea of the immortality of the soul, its fall into the body, reincarnation, and the need for purification through a specific way of life and initiation, aiming for the ultimate liberation of the soul. Their understanding fits into the broader context of Greek Mythology and religion.

What is the relationship between Orpheus and the Orphic Mysteries?

Orpheus, the legendary musician and poet of Greek Mythology, was considered the founder and first teacher of the Orphic Mysteries. Many of the sacred texts, hymns, and teachings of the cult were attributed to him. His descent into Hades and the knowledge he supposedly gained there made him an ideal figure to convey secret truths about life and death.

Did all ancient Greeks believe in the Orphic Mysteries?

No, the Orphic Mysteries were not part of the dominant, public religion of the city-states, such as the worship of the Olympian gods. They constituted a distinct, mystery cult that appealed to those seeking a more personal and profound relationship with the divine and a hope for a better afterlife. Participation was voluntary and required initiation, differing from the common worship practices of Greek Mythology.

What is the “Orphic life”?

The “Orphic life” refers to the specific way of life that initiates of the Orphic Mysteries were called to follow. It primarily involved moral and ritual purity, but the most characteristic element was abstaining from the consumption of meat (vegetarianism) and, according to some sources, from certain other foods like beans. This ascetic lifestyle was considered essential for the purification of the soul.

Is there evidence for the existence of the Orphic Mysteries?

Yes, beyond references from ancient authors (philosophers, historians), there are also archaeological findings related to the Orphic Mysteries. The most significant are the gold leaves (amulets) found in graves with instructions for the soul, as well as the Derveni Papyrus, which contains an Orphic poem and its allegorical interpretation. These findings confirm key aspects of the Orphic beliefs in Greek Mythology.

Bibliography

- Detienne, Marcel. The Writing of Orpheus: Greek Myth in Cultural Context. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

- Dimopoulos, Evangelos. “ORPHIC.” Plato, vol. 37, 1985, p. 71.

- Fry, Stephen. Heroes. Patakis Publications, 2023.

- Kakridis, Ioannis Th., ed. Greek Mythology: The Gods, Volume 1. Athens Publishing, 1986, p. 304.