In the misty, fairy-tale dawns of ancient Greek thought, where mythological imagination meets primitive philosophical inquiry, the Pelasgian creation emerges as one of the most captivating cosmogonic narratives in human tradition. This cosmogonic tradition, attributed to the Pelasgians—the original inhabitants of the Greek lands—constitutes a multi-layered myth that embodies profound symbolism regarding the genesis of the universe and human existence.

This myth narrates the cosmic creation through the actions of the Goddess Eurynome and the mysterious Ophion, offering a unique perspective on ancient Greek cosmological beliefs. Its significance lies not only in its rich symbolic dimension but also in how it reflects the deeper philosophical and cultural quests of an era when the mystery of existence sought its interpretative expression through poetic and mythological storytelling. This mythological tradition serves as an invaluable window into understanding the ancient Greek psyche and its cosmological inquiries.

The Theocosmogonic Principle: Eurynome and the Primitive Creation

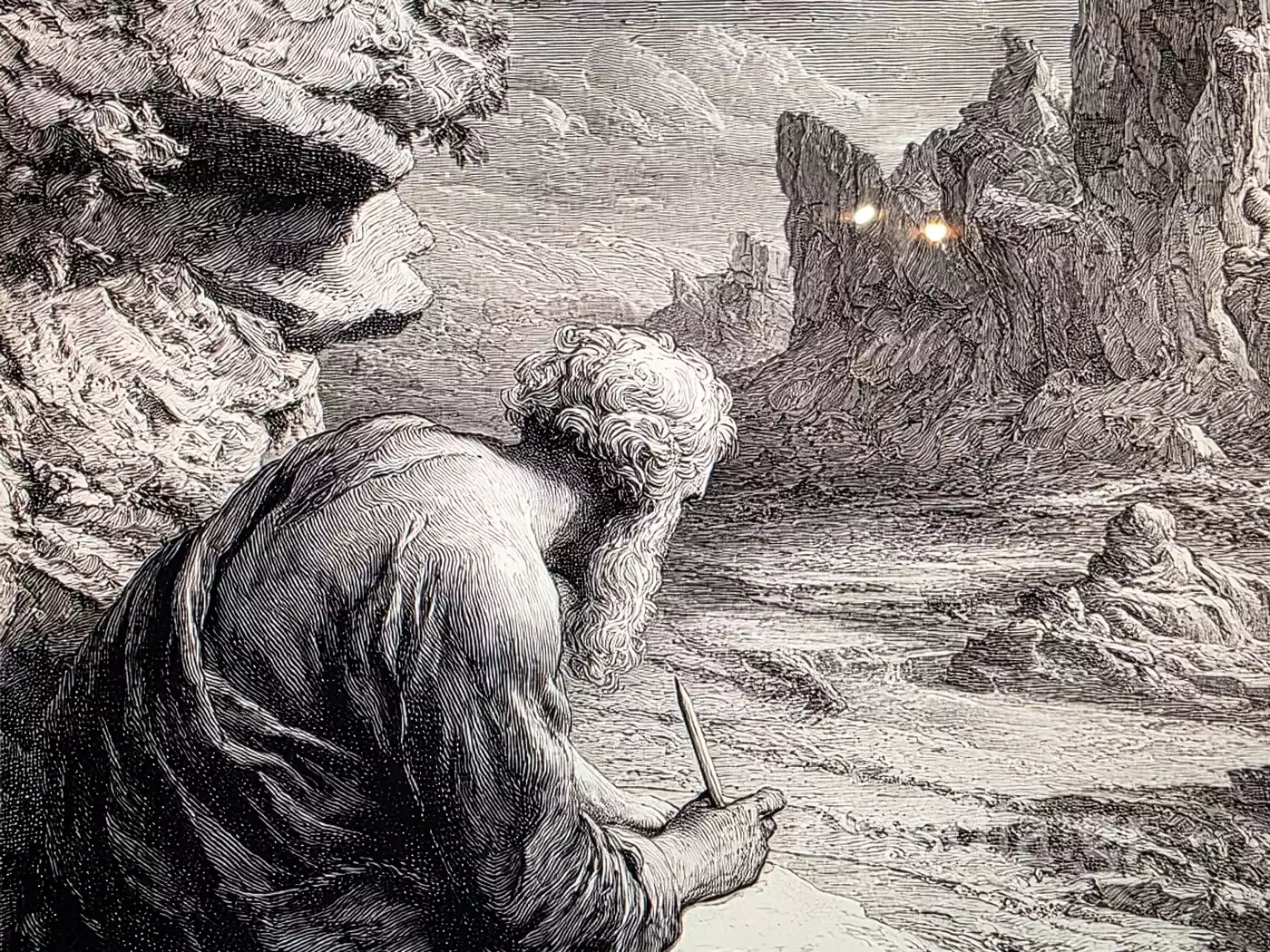

At the core of Pelasgian cosmogony stands the majestic figure of Eurynome, the Goddess of All, who rises from the primordial chaos as the embodiment of creative power. The vivid depiction of this deity, as she dances alone upon the waves of the vast ocean, separating the sea from the sky, represents one of the most life-giving and poetic verses of ancient Greek mythological thought.

Eurynome’s dance is not merely an artistic expression; it embodies the metaphysical understanding of cosmic harmony and the creative energy that permeates the universe. Through her movement, this goddess makes visible the invisible force that drives everything, while simultaneously expressing humanity’s primal need to comprehend cosmic order through anthropomorphic representations of divinity. Robert Graves’ research highlights the unique position this creator goddess holds in the pantheon of ancient Greek mythology (Graves).

The union of Eurynome with Ophion, the ancient serpent, initiates the process of cosmic creation and expresses the complementarity of opposing forces. This symbolic union reflects the ancient Greek understanding of the necessity for the harmonious coexistence of contrasting principles to achieve cosmic balance.

The Cosmic Egg and the Mysterious Genesis of the World

The pinnacle of Pelasgian cosmogony is found in the birth of the Cosmic Egg, a symbol that encapsulates the entirety of creative power in a singular and concise form. Eurynome, transforming into a dove—a symbol of peace and purity—gives birth to the Egg that contains all potential existence in the world. This transformation is not a random choice but expresses the profound connection between divine creativity and natural rebirth.

Ophion, the primordial serpent, coils seven times around the Cosmic Egg, providing protection and care until the moment of hatching. The sevenfold repetition of this wrapping is not coincidental; it reflects the ancient belief in the sacredness of the number seven, which is associated with cosmic order and the completion of cycles. This process exemplifies the dynamic relationship between divine femininity and masculine protective power.

From the hatching of the Cosmic Egg begins the story of the world, with the emergence of the sun, the moon, the planets, and the constellations, as well as the earth with its mountains, rivers, trees, and living creatures. This description reflects a holistic view of the world, where all elements of nature are parts of a unified and harmonious creation connected to the deeper cosmological beliefs of the ancient Greeks.

The Divine Conflict and the Establishment of Cosmic Order

After the completion of cosmic creation, the narrative takes a dramatic turn that reveals deeper tendencies toward dominance and balance within the divine sphere. Eurynome and Ophion ascend to Olympus, the sacred dwelling of the deities, where a fundamental conflict arises over the recognition of creative authority.

Ophion, consumed by pride and vanity, claims to be the true creator of the universe. This attempt to appropriate creative power is not merely a simple power grab but reflects a deeper struggle between the archetypal forces that govern the cosmic hierarchy. The study of ancient Greek religion reveals the complexity of these divine relationships (Burkert).

Eurynome, outraged by this affront to her divine authority, restores order through a decisive and symbolic act: she strikes Ophion and exiles him to the dark caves beneath the earth. This act is not merely a punitive measure but signifies the establishment of a cosmic order where true creative power is recognized and protected from distortions and illusions.

Ophion’s exile to the underworld serves as a rich symbol reflecting the ancient Greek understanding of the dual nature of cosmic forces. The chthonic realm is not merely a place of punishment but also a sphere where the dark and unconscious forces of the world continue to exert their influence, albeit under control and limitation.

The Creation of Planetary Forces and Cosmic Harmony

The continuation of the cosmogonic narrative reveals the wise organization of the universe through the creation of the seven planetary forces, a process that reflects the ancient Greek effort to understand astronomical phenomena through mythological categories. Eurynome, continuing her creative mission after Ophion’s exile, seeks to establish a harmonious and balanced cosmic order.

The assignment of a Titan and a Titaness to each planetary force—Theia and Hyperion for the Sun, Phoebe and Atlas for the Moon, and so forth for Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn—indicates the deep Greek belief in the necessity of balance between masculine and feminine principles for maintaining cosmic harmony.

This complementarity of genders in cosmic governance reflects an advanced theoretical understanding of the interaction of opposing forces, which foreshadows the later philosophical development of the principles of opposition and synthesis in Greek thought. The choice of specific names is not random but reflects pre-existing traditions and beliefs about the properties and characteristics associated with each celestial body. This religious tradition is an integral part of ancient Greek cosmology.

Pelasgus and the Dawn of Human Civilization

The emergence of Pelasgus as the first human, rising from the fertile soil of Arcadia, marks the transition from the cosmogonic to the anthropogenic phase of the myth and inaugurates the history of humankind in direct connection with the earth. This earthly genesis is not merely a poetic image but expresses the profound ancient Greek belief in the organic relationship between humanity and the natural environment.

The placement of human genesis in Arcadia is not coincidental, as this region was regarded by the ancient Greeks as a place of exceptional natural beauty and primitive innocence. This choice reflects the notion that the first human should appear in a space that retains the primordial purity and harmony of divine creation.

Pelasgus and his descendants represent the primal relationship between humanity and nature, learning to build huts, feed on acorns, and sew tunics from pigskin. This description of early human activities reveals an ideal primitive life, where the human community develops in harmony with the environment, free from the alienation and exploitation that characterize later eras.

This story describes the beginning of civilization not as a violent conquest of nature but as a gradual and harmonious adaptation to natural rhythms, a philosophy that resonates with contemporary ecological pursuits. The cultural legacy of the Pelasgians remains alive in the ancient Greek consciousness and continues to inspire reflection on the relationship between humanity and nature.

The Pelasgian creation, as a whole, represents a profound reflection on the fundamental questions of human existence and cosmic order. Through its rich symbolism and multi-layered narrative structure, this cosmogony offers the modern reader a unique opportunity to understand ancient Greek perceptions of divinity, nature, and humanity, while maintaining its timeless value as a source of philosophical and cultural contemplation.

Bibliography

Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 20, 2025.

Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical. Translated by John Raffan. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985.

Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Harvard University Press. Retrieved September 20, 2025.

Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths: The Complete and Definitive Edition. Internet Archive. Retrieved September 20, 2025.

Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths. London: Penguin Classics, 2012.

“The Greek Myths.” Wikipedia. Retrieved September 20, 2025.