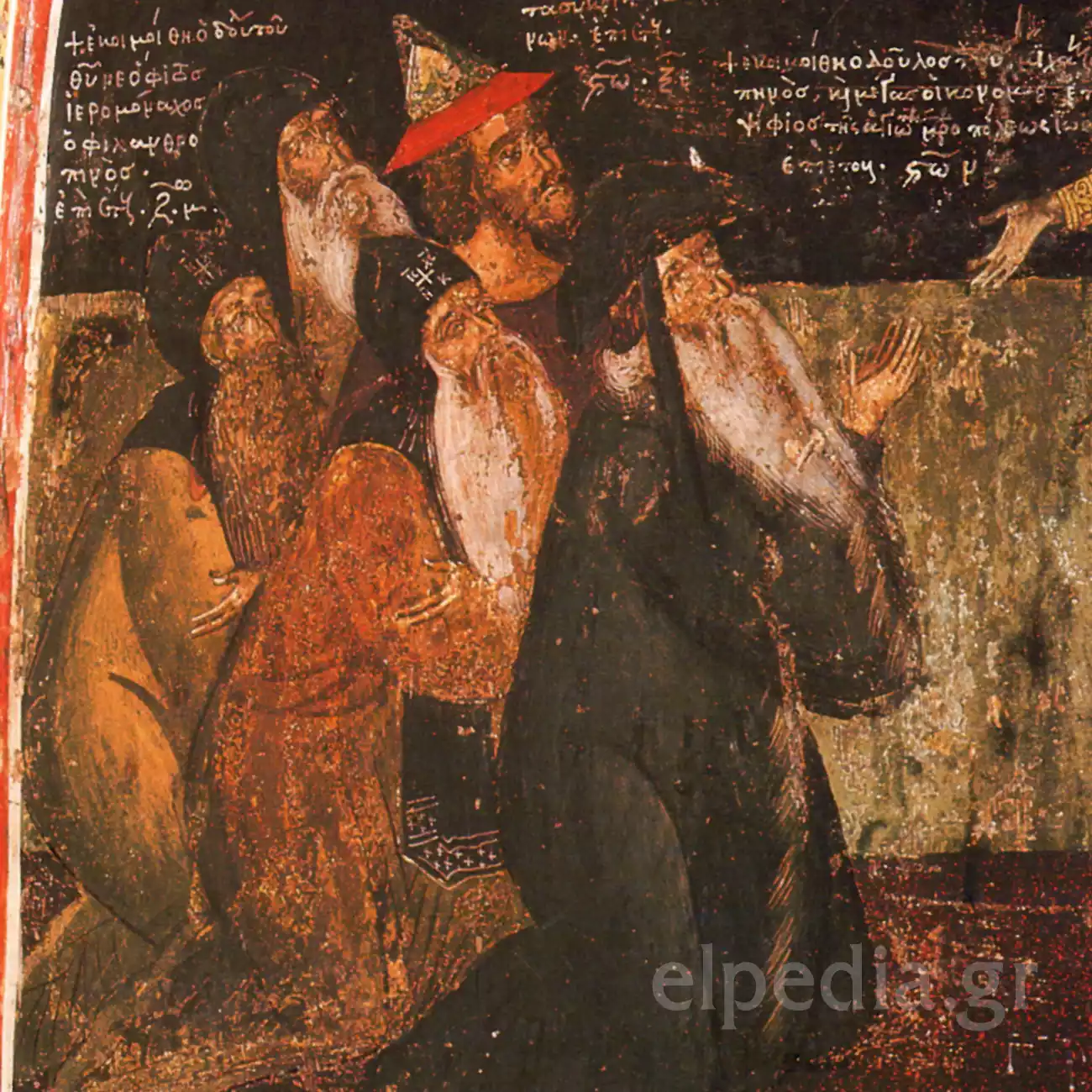

The founder’s depiction in the narthex of the Philanthropinon Monastery (16th century) shows the family members praying with the intercession of Saint Nicholas

On the small island in the lake of Ioannina, where history seems to condense under the shade of the plane trees, there lies a monastery that tells the story of a prominent Byzantine family, the Philanthropinous. The monastery’s katholikon, established in the late 13th century, was adorned three centuries later, in the 16th century, with a stunning collection of frescoes. Among them, in the narthex, stands out the founder’s depiction: a silent, almost theatrical scene where the founders themselves, family members, appear before Christ, with the intercession of Saint Nicholas. It is not merely an image of piety. It is a statement of identity, an act of remembrance, and at the same time, a profound human expression of the anxiety for salvation. The study of these works, as highlighted by the research of Myrtali Acheimastou-Potamianou, allows us to understand the first phase of post-Byzantine painting not as a mere repetition, but as a vibrant dialogue with the past in a rapidly changing world (Acheimastou-Potamianou).

Detail of the group of founders from the Philanthropinon family, depicted kneeling in reverence and humility

Spatial Composition and Divine Presence

When observing the fresco, the first sensation is one of a strict, almost architectural organization of space. The composition is invisibly divided into two levels: the earthly, below, where the mortal founders crowd together, and the heavenly, above, where Christ appears in glory. There is no landscape, no unnecessary detail. Only the deep, dark background that makes the figures stand out with an almost metaphysical intensity. This simplicity is not a sign of the painter’s weakness, but a conscious choice that serves the drama of the moment—the encounter between man and God.

Saint Nicholas, the patron of the monastery, stands imposing, wearing a multi-crossed felon, serving as the essential mediator to Christ

Saint Nicholas as Mediator

To the right of the composition, Saint Nicholas stands as the main protagonist and simultaneously the silent mediator. His figure is almost disproportionately large compared to the founders, a visual convention that emphasizes his spiritual role. He does not look at us or the Philanthropinous, but turns towards Christ, with one hand pointing to his protégés and the other open in prayer. He is the bridge between the two worlds. His multi-crossed felon, with its strict geometric patterns, creates a dazzling contrast with the dark, humble garments of the supplicants, highlighting the distinction between ecclesiastical authority and popular piety. The text unfolding in his hands is not merely a prayer; it is almost a contract of spiritual mediation, an act that validates their relationship with the divine.

The Appearance of Christ

Above the group, Christ is not depicted as the stern Pantocrator, but in a more approachable, almost personal appearance. He emerges from concentric circles of light, with arms open in a gesture of acceptance and blessing. His gaze is melancholic, full of understanding, and directed slightly downward, towards the group of believers. He holds the Gospel open, but the words do not seem to be addressed to them for reading; they appear to radiate a divine energy that envelops the entire scene. This portrayal of Christ, both robust and ethereal, raises questions about the nature of post-Byzantine theological thought that we will not address here. It is a presence that does not judge but welcomes the supplication offered through the Saint.

Close-up of Christ’s figure, whose open hands and serene face offer blessing and salvation to the faithful donors