![]()

The Tree of Jesse by Emmanuel Tzanes (1644) depicts the Holy Family in Byzantine iconographic tradition with Renaissance influences in Venice

The image “Tree of Jesse” by Emmanuel Tzanes from 1644 is an exceptional example of post-Byzantine painting in Venice. The artwork is housed in the Greek Institute of the city and presents a unique interpretation of the traditional Tree of Jesse (Lymberopoulou), focusing on Saints Joachim and Anna with the young Theotokos between them.

Tzanes highlights the genealogical continuity of salvation through the intimate presence of the Holy Family. At the center of the composition, the young Virgin symbolizes the key to divine economy, while her parents, Saints Joachim and Anna, embody the preparation and expectation of God’s people. This theme deeply permeates the ecclesiastical tradition of Byzantine art (Dalton), simultaneously expressing both the human and divine dimensions of the incarnation.

Tzanes’ technique combines traditional Byzantine elements with influences from Western Renaissance art. The golden background creates a timeless atmosphere that transcends the boundaries of the earthly realm, while the detailed rendering of faces and fabrics reveals the skill of an artist who navigated the borders of two cultural worlds.

Theological Significance of the Genealogical Tree

The Tree of Jesse is one of the most fertile symbols in Christian iconography, drawing inspiration from the prophecy of Isaiah: “And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a flower shall grow out of his roots” (Isa. 11:1). However, Tzanes chooses not to present the traditional genealogical scheme with the usual arrangement of Christ’s ancestors in tree branches. Instead, he focuses on the fundamental triad of the preparation for the incarnation: Christ’s grandparents and His mother as a child.

This choice is not incidental. The image functions as a historiated tree (Taylor) that transcends genealogical record to become a theological teaching about salvation. Saints Joachim and Anna, parents of the Theotokos, appear here not only as historical figures but as typological representations that foreshadow divine economy. Their presence alongside the young Virgin creates an intimacy that approaches the mystery of the Theotokos through the human experience of family.

The artist places angels at the top of the composition holding ribbons with inscriptions, referencing the liturgical and hymnographic tradition of the Church. This element connects the image to the act of worship, making it not merely a work of art for viewing but a means of prayer and theological teaching. The architectural elements in the background—buildings reminiscent of Bethlehem and Jerusalem—situate the theme within a broader eschatological context that embraces the past, present, and future of salvation.

Saint Joachim appears as a figure of deep spirituality in Tzanes’ work, showing protective affection towards the young Virgin and reverent recognition

Iconographic Influences and Artistic Technique

Emmanuel Tzanes (Chatzouli) emerges in this work as an artist who moves fluidly between Eastern and Western traditions. His choice to depict the Virgin as a young girl instead of the usual Byzantine type of mother reflects influences from Western Renaissance art while maintaining Eastern theological symbolism.

The colors of the composition—the red of the garments, the gold of the background, the green of the young Theotokos—create a harmony that enhances the symbolic content. The red alludes to blood and sacrifice, the gold to divine glory, while the green symbolizes life and youth. This color choice is not merely decorative but theological, as each color carries specific meanings in Byzantine iconographic tradition.

Tzanes’ technique reveals an artist who has assimilated Western innovations without abandoning the theological essence of Eastern art. The plasticity of the faces, the perspective of the space, and the detailed rendering of fabrics demonstrate awareness of Italian techniques, while the overall composition, the symbolic use of space, and the theological density remain faithful to the Byzantine tradition.

The Virgin’s Expression: Theology through Physiognomy

The face of the young Theotokos serves as the emotional and theological center of the composition. Tzanes presents her not as the traditional mature Byzantine Virgin but as an adolescent figure that combines innocence with profound inner maturity. Her large, expressive eyes gaze towards the viewer, simultaneously embracing childlike simplicity and divine wisdom.

This choice reflects a deep theological understanding of the mystery of the incarnation. The young age of the Virgin is not merely historical accuracy but a symbolic statement: salvation comes through the new, the pure, the untainted by the conventions of the world. The red mantle that envelops her alludes to the future testimony of her Son, while the golden aura around her head emphasizes the already existing divine grace.

The Virgin’s mouth, small and delicately formed, remains closed, suggesting the silence of the mystery she bears. This silence is not emptiness but fullness—the silence of one who has accepted to become a vessel of divine economy. The arrangement of her hands, one slightly raised towards Joachim, the other towards Anna, creates a movement that symbolizes her mediation between the past and the future.

Saint Anne as the embodiment of maternal wisdom in the Tree of Jesse wears a red mantle symbolizing love and the divine grace of Christ’s genealogy

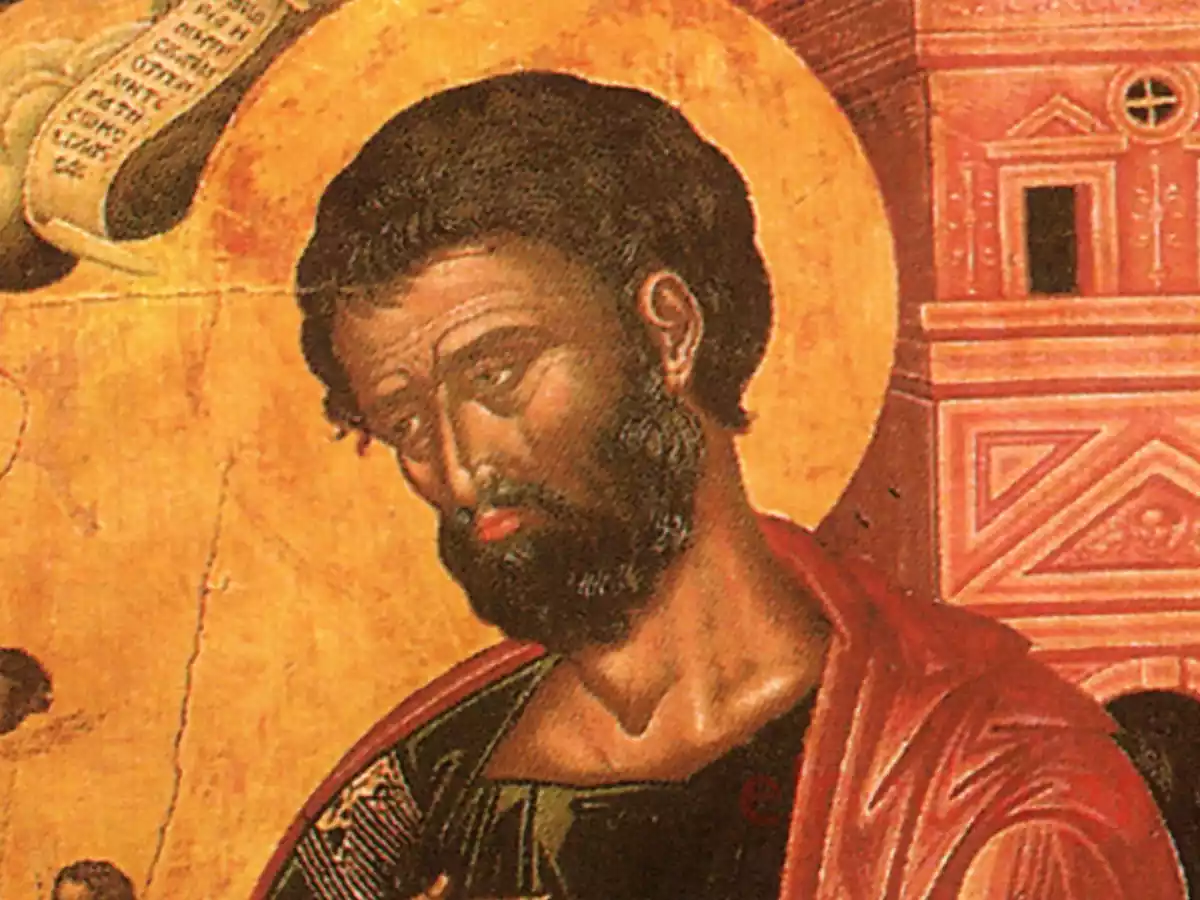

The Figure of Saint Joachim: Paternal Dignity

Saint Joachim is portrayed as a figure of deep spirituality and paternal dignity. His face, with its characteristic beard and deep eyes, reflects the wisdom of age and the faith of one who has witnessed the fulfillment of divine promises. His bronzed skin and the detailed rendering of wrinkles reveal a man who has lived, suffered, and hoped.

The way Tzanes depicts Joachim transcends simple portraiture. His body posture, slightly inclined towards the young Theotokos, expresses the protective affection of a grandfather as well as the reverent recognition of the mystery his granddaughter carries. His hand, placed on his chest, is a gesture that alludes to inner emotion and spiritual reverence.

His garments—the red outer robe and the green inner tunic—reflect his dual identity: a man of the world yet an instrument of divine economy. The detailed rendering of the fabrics, with their folds naturally following the movements of the body, showcases Tzanes’ technical skill and his effort to embody the spiritual through the material.

The Form of Saint Anne: Maternal Wisdom and Spiritual Maturity

Saint Anne appears in the image as the embodiment of maternal wisdom that bridges generations and maintains the continuity of faith. The red mantle that envelops her, adorned with golden decorations at the edges, creates a halo around her face that underscores the divine grace that permeates her. The choice of color is not incidental: red symbolizes love, sacrifice, and the royal dignity of one chosen to be the mother of the Theotokos.

Her face reflects a deep inner life stemming from the spiritual experience of motherhood and prayer. Her features—the eyes with their melancholic wisdom, the mouth remaining in a silent prayer expression—reveal a personality that has absorbed the mysteries of divine economy through daily life. The slight tilt of her head towards the young Theotokos expresses ongoing maternal care and reverent recognition of her daughter’s extraordinary calling.

The arrangement of Anne’s hands creates a gesture of offering and blessing that extends towards the young Virgin. This gesture transcends maternal affection to become a theological statement: Anne is presented not only as a mother but as one who offers to the world the future Mother of God. Her placement in the composition, on equal footing with Joachim, reflects the theological dignity of women in the work of salvation, as expressed through Byzantine tradition.

The image of the Tree of Jesse by Emmanuel Tzanes is a rare composition that combines the theological depth of Byzantine tradition with the artistic innovation of the Renaissance. It serves simultaneously as an ecclesiastical teaching (Kirchhainer), a prayerful image, and an artistic achievement. Tzanes’ unique perspective on the traditional theme creates an image that speaks to the soul of the modern viewer with the same intensity it addressed the faithful of the 17th century. Through the intimate presentation of the Holy Family, the work approaches the mystery of the incarnation not as a distant theological truth but as a living experience that touches the depths of human existence. In this particular image, salvation is not an abstract concept but the specific story of a family that became a vessel of divine grace.

![]()

The young Theotokos at the center of the composition symbolizes the key to divine economy in the Tree of Jesse with expressive eyes and spiritual maturity

Bibliography

Arentzen, T., Burrus, V. and Peers, G., Byzantine Tree Life (Springer).

Chatzouli, G., ‘The Icon of the Virgin and the Child with Archangels, and Saints. Work of the Artist-Priest Emmanuel Tzanes (1668)’, Konštantínove listy, 2022.

Chittenden, Jacqueline and Seltman, Charles Theodore, Greek Art: A Commemorative Catalogue of an Exhibition Held (Royal Academy of Arts, 1947).

Dalton, Ormonde Maddock, Byzantine Art and Archaeology (1911), p. 414.

Kirchhainer, K., ‘Die Verkündigungs-Ikone des Emmanuel Tzanes im Ikonen-Museum Frankfurt’, Δελτίον της Χριστιανικής Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, 2010.

Lymberopoulou, Angeliki and Duits, Rembrandt, Byzantine Art and Renaissance Europe (2016).

Taylor, M.D., ‘A Historiated Tree of Jesse’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 1980.