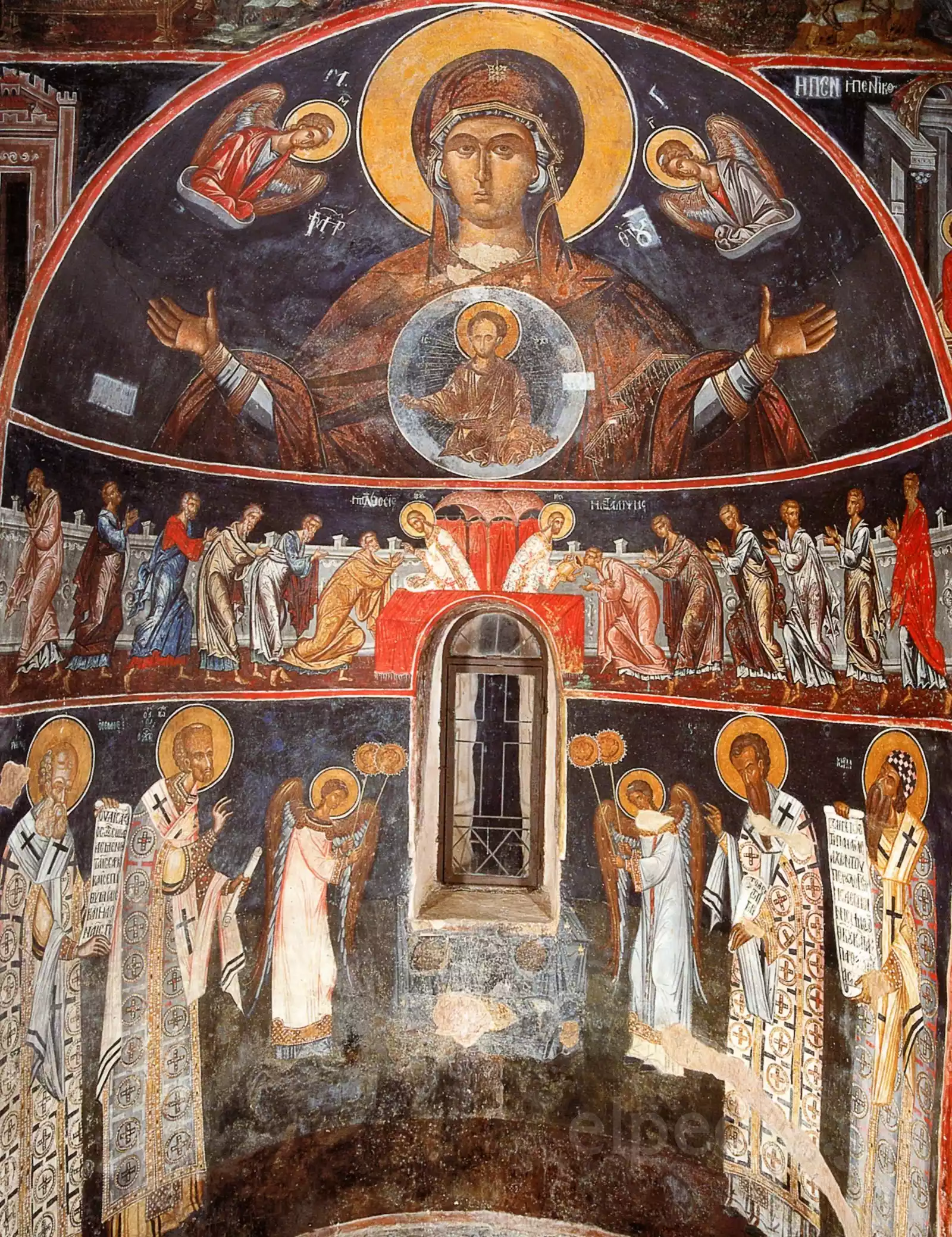

The tripartite arrangement of the apse combines heavenly glory, historical divine communion, and liturgical order in the frescoes of the Monastery of Philanthropinon.

On the island, the humidity seems to soak not just the stone but also time itself. It creates a strange sensation of both weight and uplift as you cross the threshold. This is not merely a place of worship but a shell of memory. In Byzantine art, things are rarely what they seem at first glance. You need to pause. Wait for the light to fall just right, or perhaps allow your eyes to adjust to the dimness.

Here, within the interior decor, history is not written with ink but with colors that have somehow endured – who knows how? – the ravages of time and human neglect. Your gaze instinctively rises upwards. It’s as if there is an invisible line guiding you to the apse. Something significant occurs there. Not loud. Significant in its silence. The art in this monument serves as a record of a society that learned to communicate through symbols, perhaps because words were scarce or dangerous.

You see the figures and wonder about the artisan. How did he feel as he spread the lime? Did he realize he was creating history, or was he simply doing his job? Probably the latter. Yet, the former emerged. An art that does not shout but whispers intensely. It’s hard to explain to someone who hasn’t stood before such a wall, to feel the texture of the image looking back at them.

Artistic Narrative and Form Dynamics in the Sanctuary

The gaze is fixed on the apse. It serves as both the vanishing point and the point of return. Here, the Platytera reigns. A figure that occupies space not so much with her bulk but with her presence. She is the Blachernae. Her hands are raised. A gesture of supplication, experts say. I see it as a gesture of openness. An embrace that hangs in the air, ready to either encompass the world or set it free. In her chest, Christ in glory. He is not an infant here; he embodies the Word, a theological statement painted in ochre and gold.

She is flanked by the Archangels, Michael and Gabriel. They stand respectfully. Not motionless, however. There is a slight lean in their bodies, a submission to the rhythm of the central figure. The Virgin functions here as a shelter. A refuge. Perhaps it captures the most human need depicted on the wall: the need for protection. And the painting responds. The curves are soft, avoiding harshness, creating a sense of safety.

The Rhythmic Movement of the Apostolic Communion

Lowering your gaze, the calmness of the apex gives way to movement. In the zone just below, the Communion of the Apostles unfolds. Here, the painter decided to play with rhythm. The theme is familiar: the Transmission and the Communion. But pay attention to their feet. The stepping.

The scene is divided in two. Two semi-choirs. It resembles a theatrical stage where the actors know exactly where to step. Christ appears twice, beneath a canopy, an architectural structure that defines the space, adding depth to a surface that is, by definition, flat. He wears white, priestly vestments. The white here is not merely a color; it is light. It stands out against the earthy tones of the others.

The disciples approach in groups of six. There is an anticipation in their bodies. Outstretched hands, bodies leaning slightly forward. Peter and John, the foremost, are the first to receive the bread and wine. What’s interesting is how the artist handled the sense of community. They are not a mass of people. Each has their own identity, their own “breath” within the composition, even as they follow the same path.

And then, there is that detail that disrupts the balance. On the far left. Judas. He is leaving. His body turns towards the exit, his head bowed. He puts the bread in his mouth, but his thoughts are elsewhere. On betrayal? On escape? His back is turned to the viewer, a visual aversion that creates tension. It is the “crack” in the harmony of the scene. The painter was unafraid to show this ugliness, this human failure, alongside the sacred. It’s shocking, when you think about it. Art does not always beautify; sometimes it reveals.

The Melismos and the Stillness of the Hierarchs

Lower down, at the base of the apse, time seems to freeze once more. Here we have the Melismos. Four large figures, the Hierarchs, flank the Holy Table. John Chrysostom, Gregory the Theologian, Basil the Great, and Cyril of Alexandria. They stand, or rather serve, with a gravity befitting their vestments.

They wear multi-crossed sakkos, heavy fabrics with geometric patterns that the artist rendered with precision. They hold the lectionaries, those elongated books containing the texts of the liturgy. Here, the writing becomes part of the image. The letters are not easily readable from afar, but their presence signifies the validity of the mystery.

Two angels, dressed as deacons, hold the fans with the six-winged seraphim above the Table. The symmetry is absolute. In contrast to the movement of the Apostles above, here order prevails. An order that is almost otherworldly. The faces of the Hierarchs are stern, ascetic, with those large eyes typical of Byzantine style that seem to gaze beyond the viewer, into an endless time.

Color plays a crucial role here. The shades of the vestments, the gold in the halos, the white of the Holy Table, all compose a whole that shines even in the dim light. They are works of art, indeed. But they are also testimonies of an era when beauty was the only way to approach the unknown.

Studying these works, as well as other iconographic representations in the area, shows us that art in Ioannina during that period was neither provincial nor isolated. It had knowledge, it had technique, and above all, it had a perspective.

Looking at the apse as a whole, you grasp the wisdom of the composition. From the heavenly calm of the Platytera, to the historical movement of the Apostles, and finally to the liturgical stability of the Hierarchs. Three levels, three worlds coexisting on the same wall. And you, the viewer, stand small before this scale, trying to decipher the gazes that have been watching you for centuries. Ultimately, it is a meeting. Silent, yet defining.