The art of Crete, particularly during the 16th century, constitutes a field of perpetual, almost agonising, osmosis; a place where the austere, transcendental geometry of the Byzantine tradition encounters—not always peacefully, it must be said—the new anxieties of Italian humanism, the theatricality and psychological realism that the Renaissance brought with it. Upon this crossroad, on this fertile ground of contradictions, was born the Appearance of the Risen Christ to the Magdalene, a portable icon of exceptional artistry and theological depth, crafted by an anonymous, yet great, Cretan painter. The work, today housed in the Museum of Icons in Dubrovnik, is not merely a hagiography; it is a theological essay written with colour and light, a study on the untouchable and the human, on the distance that both separates and unites the divine with the earthly. I recall the first time I faced this icon, not in some cold museum catalogue, but in a reproduction that captivated me with its internal tension, a tension that springs precisely from this tender, yet absolute, denial of touch. It is a work that negotiates limits. The limits of faith, of the flesh, of understanding. And it does so using a visual language that, while firmly rooted in tradition, does not hesitate to whisper something new, something that heralds the great compositions of Theotokopoulos. Byzantine painting did not end in 1453; it was transformed, and here, in Crete, it found one of its most brilliant expressive vehicles (Koumbaraki-Panselinou).

The Stagecraft of the Divine Drama: Space and Time in the Cretan Icon

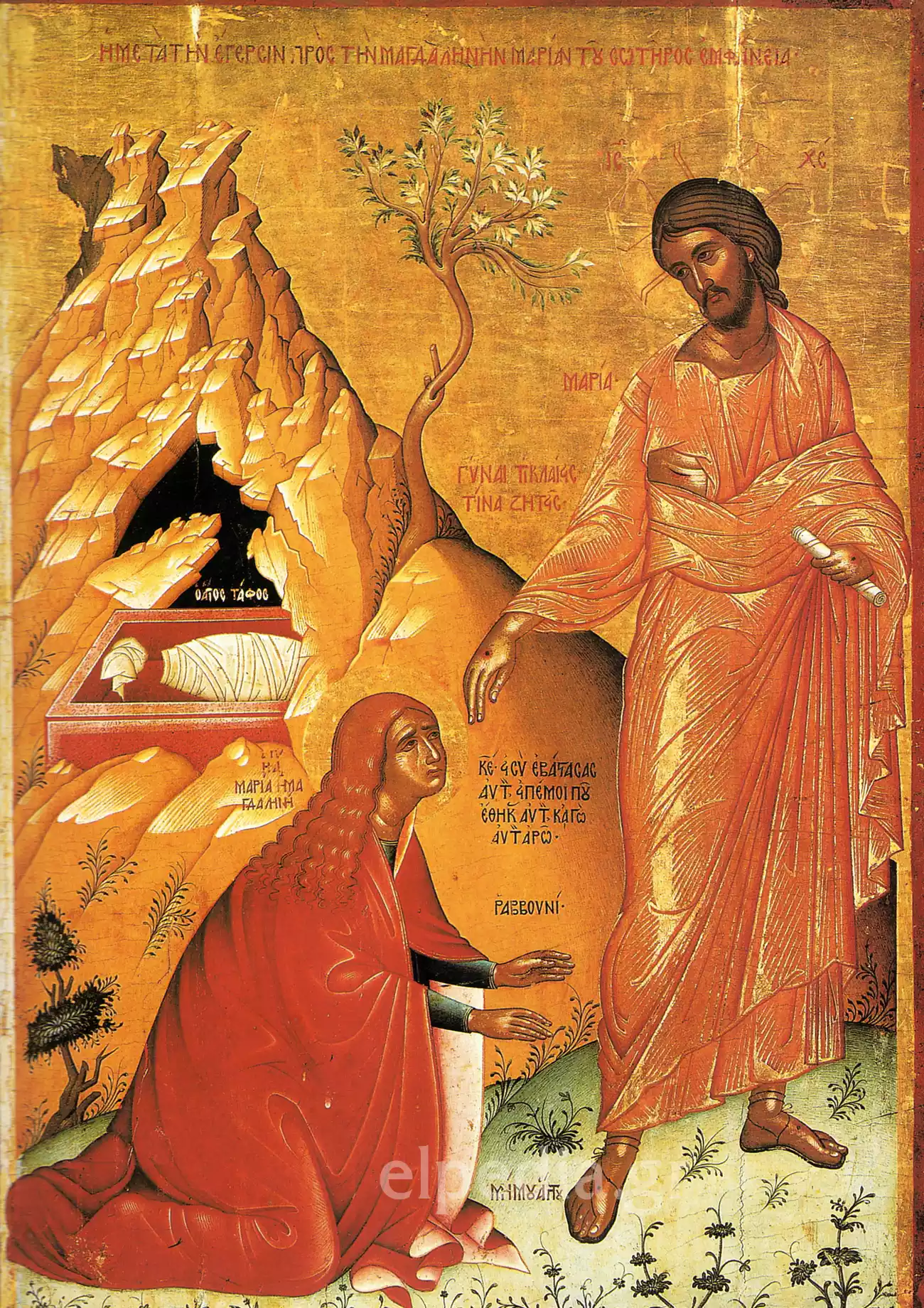

The anonymous painter sets his scene with a wisdom that transcends simple iconographic convention. We do not have here a neutral gold ground. Or rather, the gold ground, the symbol of timeless, divine light, exists, but it is confined, demarcated by a landscape that is intensely dramatic, almost hostile. A rock. Angular, inhospitable, sculpted in a manner reminiscent of the most austere Palaiologan compositions, it dominates the left section. The cave of the Tomb gapes, a black, menacing opening that, however, no longer holds the dead, but instead reveals the linen cloths, the shrouds, folded neatly, a sign of a departure that was orderly, conscious, not a hasty escape or theft. Within the darkness, the white fabrics phosphoresce, witnesses to an absence. The space here is not realistic; it does not obey the laws of perspective that already held sway in Italy. It is a theological space, a space that functions symbolically. The rock, hard and barren, is the world of death, the world of the Old Covenant, which has now been ruptured by the light of the Resurrection. And precisely above the encounter, a small, almost desiccated tree sprouts stubbornly, a delicate, fragile allusion to the wood of the Cross that became the Tree of Life. Nothing is accidental. The composition is invisibly divided by two diagonal axes: one is defined by the gaze of Christ towards the Magdalene, and the other by the movement of their hands, a movement that never completes, that remains suspended, charged with all the intensity of the moment. This management of space, where every element, from the smallest shrub to the imposing mass of the rock, serves the central theological message, is a legacy of the great Byzantine tradition, filtered, however, through a new sense of drama.

The Protagonists of the Holy Encounter: Theology and Human Passion

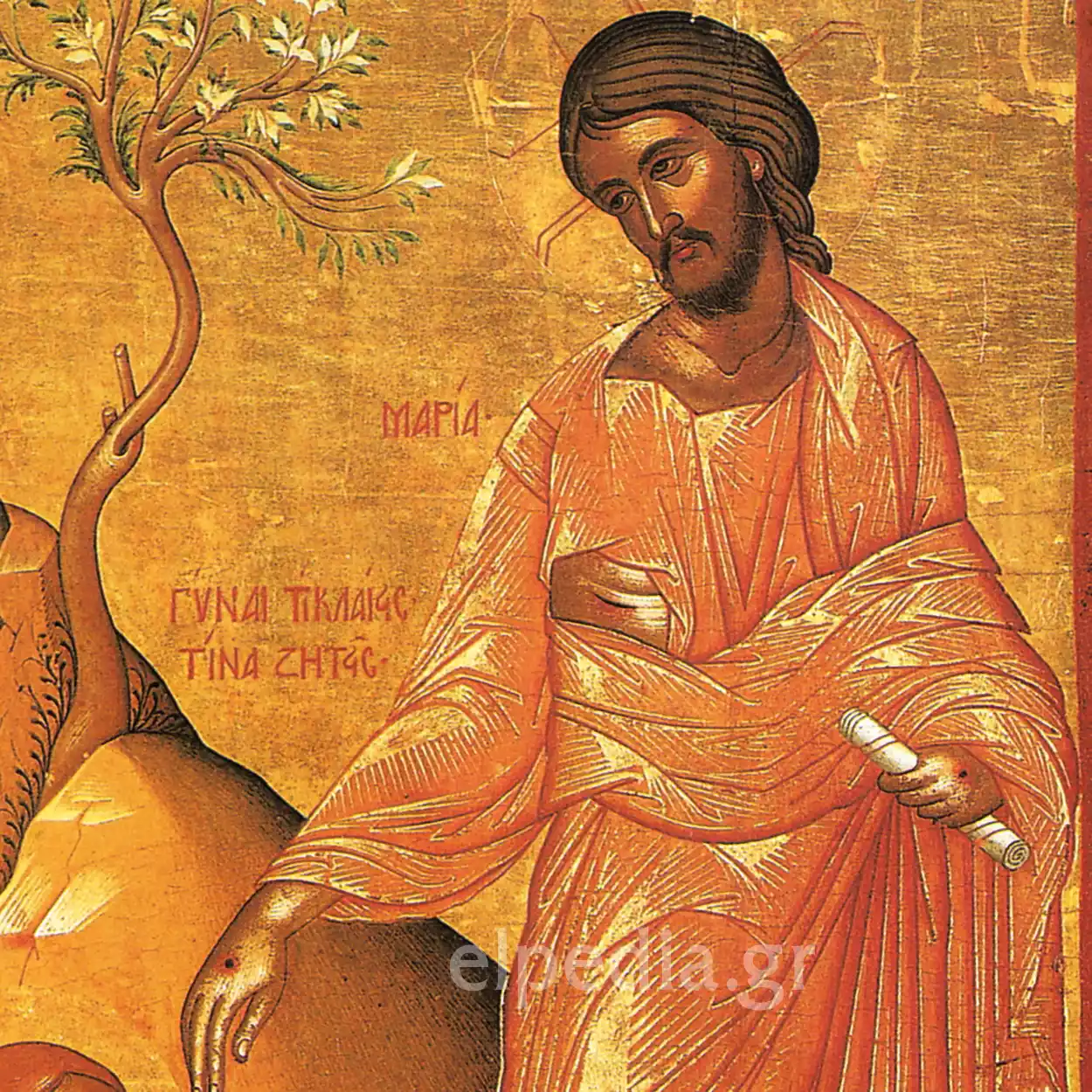

And we arrive at the protagonists. At the epicentre of this cosmic drama. Christ, on the right, stands erect, serene, but not distant. His body, draped in a himation of orange and red hues, is rendered with a plasticity and volume that betray a knowledge of Western art. The folds of the garment are not merely linear and decorative, as in earlier Byzantine art, but follow and reveal the structure of the body beneath, giving it substance, weight. He holds in his left hand a scroll, a symbol of the new teaching, and his right hand, the very centre of the entire icon, moves downwards in a gesture of both prohibition and blessing. His face, with its gentle, almost melancholic features, looks upon the Magdalene with an expression of infinite compassion, but also of divine authority. He is the Lord of History, who has already conquered death and now belongs to another sphere, incorruptible and immaterial.

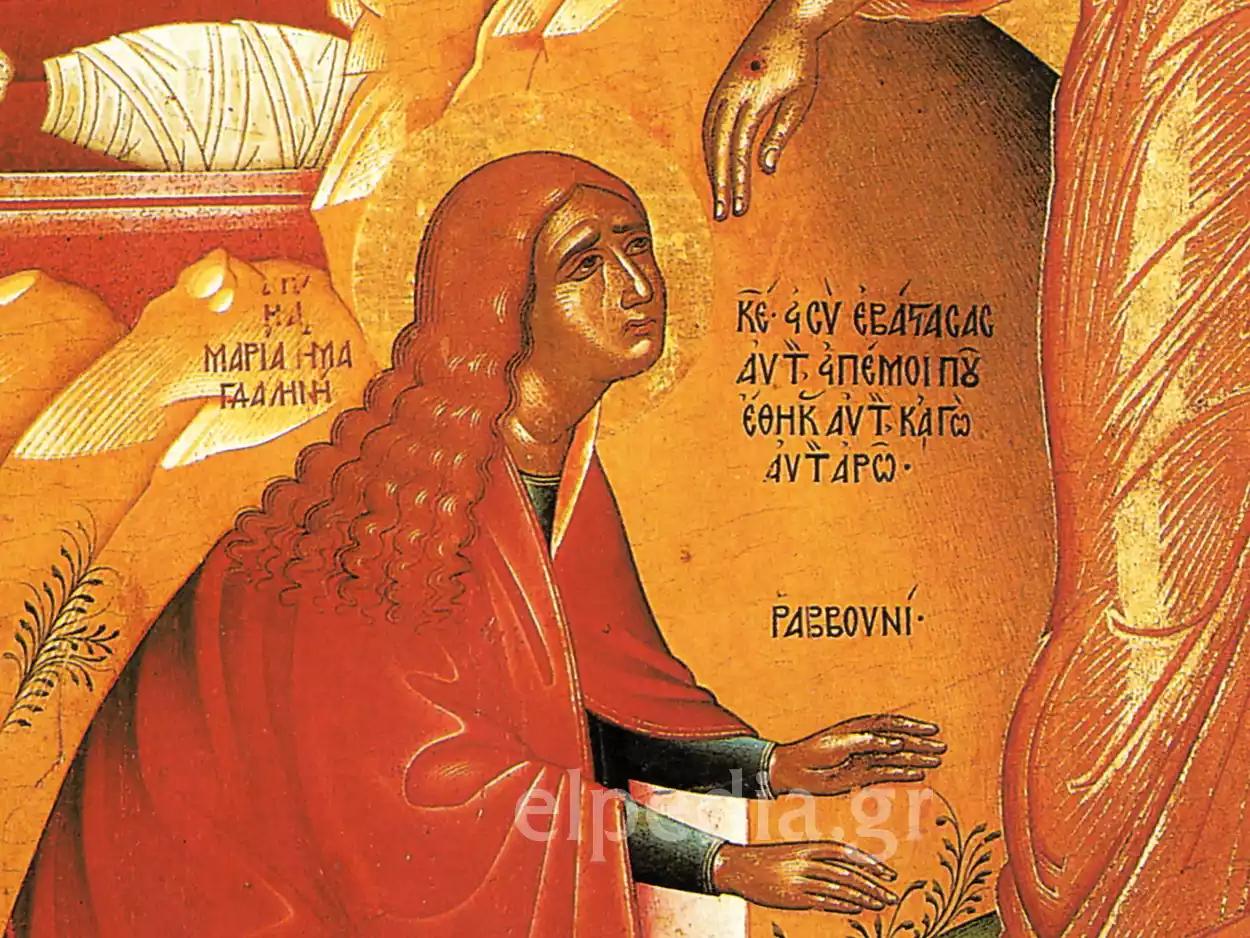

Opposite him, kneeling, almost prostrate on the ground, is Mary Magdalene. A figure entirely given over to passion, to the human, insuperable desire to touch, to confirm by feel what her eyes cannot believe. She wears a deep red maphorion, the colour of blood, of sacrifice, but also of human emotion. Her hands are outstretched, open, in a gesture of longing that is brought to an abrupt halt, mere centimetres from the Teacher’s body. Her entire posture—the kneeling, the slight inclination of the head, the gaze raised in awe and wonder—is a cry. A cry that meets the calm, yet unyielding, command: “Touch me not”. The painter here achieves something astonishing: he renders visually a theological condition. The transition from a faith based on sensory experience to a faith founded on the word and on a spiritual relationship. The interaction of the two cultural traditions, East and West, is evident in such works, as is pointed out in a relevant study on the relationship between Byzantine art and Renaissance Europe (Lymberopoulou and Duits). The dialogue between human passion and divine serenity could not have been rendered with greater lucidity.

Concluding Reflections

In the end, what is this icon? It is, I would dare to say, a visual poem about distance. The sacred distance that must be traversed not with the hands, but with the heart. The 16th-century Cretan painter, this anonymous master, does not simply illustrate a Gospel episode. He comments on the nature of faith itself. By synthesising the severity of the Byzantine form with the psychological intensity taught by the West, he creates a work that transcends the limits of its era. It invites us to look beyond the surface, beyond the gold leaf and the brilliant colours, and to contemplate the fine line that separates knowledge from faith, touch from trust. It is an icon that offers no easy answers; on the contrary, it poses questions. And perhaps it is precisely in this that its timeless power lies…

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the significance of the phrase “Noli me tangere” in this Cretan icon?

In this particular Cretan icon, the phrase “Noli me tangere” (or “Μη μου άπτου” in the original Greek) is not a simple rejection. It symbolises the new, spiritual state of the Risen Christ, whose body no longer belongs to the corruptible, material world. It is an invitation to the Magdalene, and by extension to every believer, to transition from a relationship based on sensory, physical contact to one founded on faith and spiritual union.

Which key features of the 16th-century Cretan School are visible in this artwork?

This icon is a quintessential example of the 16th-century Cretan School. We can clearly discern the survival of Byzantine elements, such as the gold ground and the schematic rendering of the landscape. Simultaneously, influences from the Italian Renaissance are evident, particularly in the plasticity of the figures, the sense of volume of the bodies beneath the drapery, and the intense psychological drama of the scene, which are all characteristics of the mature phase of this great school.

Why is the figure of Mary Magdalene depicted with such emotional intensity?

The emotional intensity of Mary Magdalene in the analysis of this Cretan icon is deliberate. She represents human nature at its most authentic moment: the longing, the wonder, and the love before a miracle. The painter uses her kneeling, almost ecstatic posture and her expressive face to create a powerful contrast with the serene, transcendental figure of Christ, thus heightening the drama of the encounter between the divine and the human.

What is the role of the landscape and the empty tomb in this Noli me tangere icon?

The landscape in the “Noli me tangere” icon is not merely decorative. The angular, barren rock symbolises the world of death, which has now been defeated. The empty tomb, with its neatly folded shrouds, acts as the irrefutable witness to the Resurrection. Every element of the space is theologically charged and serves the narrative, transforming the landscape into an active participant in the divine drama rather than a passive backdrop.

How does this 16th-century icon blend Byzantine tradition with Western influences?

This blend is the very essence of the Cretan School of iconography. The Byzantine tradition is present in the austere composition, the use of a gold background to symbolise divine light, and the adherence to iconographic canons. Western, Renaissance influences are found in the attempt to render volume, the naturalism of certain gestures, and, above all, the focus on the psychological dimension and human emotion, creating a unique artistic synthesis.

Bibliography

Koumbaraki-Panselinou, Nausica. Vyzantinī zōgraphikī: ē Vyzantinī koinōnia kai oi eikones tēs. Kentro Vyzantinōn Ereunōn, 2000.

Lymberopoulou, Angeliki, and Rembrandt Duits, editors. Byzantine Art and Renaissance Europe. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013.